Martial Law is still happening with great sophistication and innovation

Martial Law is still happening with great sophistication and innovation

Personal Account: CONNIE SORIO

I live in Toronto, Ontario. I have four sons and three grandchildren. We moved to Canada from the Philippines in 1989 at the peak of the series of coup attempts staged by some members and leadership of the Philippine military to destabilize the Philippine government under the presidency of then Corazon Aquino.

I am currently the Partnerships Coordinator for Asia-Pacific at KAIROS: Canadian Ecumenical Justice Initiatives and member of the International Coordinating Body of the International Migrants Alliance, a global formation of migrant workers organizations from different countries asserting for the protection and promotion of their rights as human beings and not as slaves or commodities.

As the Asia-Pacific regional coordinator for partnerships at KAIROS, it provides me the opportunity to work and advocate on social issues that continue to plague the Philippines which has commonalities with other Asia-Pacific countries. It allows me to bring these issues to Canada and mobilize support and solidarity from among churches and its constituents, and the Canadian general public i to respond especially if the injustices resulting to further aggravation of the already fragile human rights situation are directly connected to Canadian trade and investment.

When KAIROS was still receiving funding from the Canadian International Development Agency, my main responsibility was to oversee and manage the CIDA funded program in the region which included partners’ visits, program monitoring and evaluation, and reporting to CIDA.

On my free time (since I came in 1989) I am an active member of the solidarity group to the Philippines, an advocate for the rights and welfare of live-in caregivers and temporary foreign workers both at the policy level and community organizing collaborating with different migrant workers organizations. As member of the International Coordinating Body of the International Migrants Alliance, the thrust is assert the dignity of workers with inherent human rights and not treated as slaves or commodities. This is very important and relevant here in Canada as we are seeing a tremendous increase of temporary foreign workers.

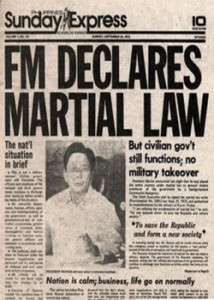

Early martial law

I was in elementary grade living in a protected environment in the province at that time so I don’t have a vivid recollection of how people in my immediate circle reacted when Martial Law was declared. I remember though being gathered in the school yard and the town Mayor (my late uncle) telling us about the fight against the communist insurgents or “enemies of the state” and the “evils of communism”. Then I remembered my late father organizing proper burials of unclaimed slain “communist insurgents” who were killed during military operations and were brought to the town center for relatives to claim. I cannot remember how I felt during that time except to know that what was happening was wrong. In retrospect, that experience might have actually triggered curiosity and interest to find out more why some people were fighting and willing to die in the process.

Initial involvement

It was towards the lifting of Martial Law that I got involved. Having finished secondary school in the province, I moved to Manila for my university studies. My parents avoided me going to UP because it was infested with and breeding activists, so I ended up in a very conservative college in Quezon City. My immediate circle of friends was daughters and sons of hacienderos from Bacolod, Quezon Province and affluent families from other provinces. We were able to easily identify the activists in the school and vowed to stay away from them. To make the story short, I was the weak link in that group, I was the first to be invited and given orientation on student issues and how students are organizing and responding to assert collective rights that were stripped when ML was declared. I started becoming active during the election of the first Batasang Pambansa, supporting and campaigning for candidates like the late Ninoy Aquino and others

I was elected as the founding national secretary of the National League of Students of the Philippines predecessor of now known as LFS (League of Filipino Students) in 1979. It was during this time that the student/youth movement started to regroup, reorganize and rechannel youth energy which was for several years spent with fraternity related activities like hazing, fraternity wars, etc., towards asserting student rights and welfare. We started to lead school boycotts and at the same time negotiated peace and unity among different school fraternities. We started national campaigns to oppose the increase in tuition fees, lack of facilities and quality education and right of students to organize student bodies. It was during this time that I experienced fascism and political suppression.

Arrest orders

I was named in several arrest orders, at that time called ASSO (Arrest, Search and Seizure Orders), placed under intelligence surveillance, and experienced harassment and intimidation.

Fortunately I was not arrested but half of the leadership of the NLSP was arrested and detained during the official years of Martial Law. I say “official” because even though ML was lifted in 1981, the very same military structures and mentality of crushing any legitimate dissent were still in place.

In fact my actual brush with the military face to face was in 1981, when our house was raided by the military it being an alleged subversive headquarters. My husband at that time (we are separated now) was arrested, put in an undisclosed detention for almost a week, tortured and interrogated for my whereabouts. I was in hiding for more than six months pregnant with my second child while my first child stayed with my in-laws.

When I finally surfaced with the legal support of the Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG), I was interrogated, not allowed to leave the country, placed under house arrest and was ordered to report to the arresting group regularly and on call (they can call me in anytime they desired to).

House arrest

My lawyer and friends in detention negotiated for my safe coming out as I was about to give birth then to our second child. The condition for my safe coming out was that I will not accompanied by any lawyer and that I should cooperate in responding to their questions (interrogation). I said “safe” because the bottom line of the negotiation was that I will not be arrested and detained. Although at that time, I really did not care. I was tired of having to move from one place to another and sort of exposing friends who provided me shelter at risk.

During interrogation, I was given the stick and carrot approach which was standard, I think. There were two officers, one pretending to be very understanding, sympathetic and sort of offered his shoulders to cry on. The other one was the pushy, rude and threatening one who asked questions rapidly, repeatedly and with menace to intimidate me while the other one was gentle and made you easily forget that you were being interrogated and let your guard down.

I was called in for interrogation several times, made sure I knew I was being followed. For several times they visited me in my home and all sorts of other stuff. At one point, one of the intelligence officers even volunteered as godfather to our second son.

What struck me during these “conversations” was their broad knowledge of my family background, some of my relatives and their “attempt” to have my family stop me from my involvement before they stepped in. I was aware of that incident when I went home to the province not knowing that I was followed. I only stayed for a couple of days and after my return to Manila, my mother arrived the following day diplomatically asking me to go back home. Coming back home with her, I found out that an intelligence officer talked to my uncle (the town mayor) whom the intelligence officer had mistaken as my father. My uncle was told of my “subversive” activities and was given an ultimatum that if my family could not stop me, then they will, in a threatening manner. I explained to my family my passion to assert student rights and welfare and get the quality of education that we deserve after having to pay those exorbitant tuition fees. Anyway, I was sort of given the blessing to go back to Manila and continue my studies. That part of the intelligence group had this experience documented in their dossier.

Task Force Detainees

As mentioned, I was not officially arrested, detained and charged in any courts of law, but my former husband was. While working for his release together with families of other political prisoners, I got involved with the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines and at some point became the officer in charge (executive director) of KAPATID, an organization of families and friends for the release and amnesty of political prisoners in the Philippines.

My experience actually affirmed that gnawing feeling I had in my gut when I first heard of Martial Law during my elementary years and seeing those unclaimed bodies killed during military operations. While my personal experience was not as harsh and brutal compared to what others experienced, I had friends during my student activism days who were murdered, forcibly disappeared, tortured and raped and the only justification given by the military perpetrators was that the victims were allegedly members of the underground movement or connected to the communist insurgency.

State brutality

Any law that officially legitimizes the use of state brutality and force to suppress and curtail people’s right to dissent and express their opposition or resistance in the name of national security is bad to its people and country in general. Nothing can justify this. Horrific stories of torture, killings, disappearances and other human rights violations have been documented in various formats which very clearly showed that people, poor and marginalized people fighting for their rights and demanding for better economic policies that favors Filipinos instead of foreign interest were the hardest hit during Martial Law.

Resilience

If there is any positive learning that can be gleaned from that experience, it is the collective resilience of the people in the left, standing up and fighting back despite the heavy toll on its membership. Unfortunately, quite a number of those involved and suffered in the hands of the military during the Martial Laws years are not politically active anymore and are now content to muse over the experience romanticizing it rather than in an analytical lense and accept that fact that what happened during Martial is still happening now – with great sophistication and innovation.

To remember the horrors of the Martial Law years is to continue to fight for people’s rights and struggle for national democracy and liberation. The same level of organizing and solidarity building done to dismantle Martial Law and expose the impunity enjoyed by the military (until now) that time should continue, if not in higher degree because the condition of the people economically and politically did not fundamentally improve since then.

Comments (2)

Categories