Teach our children to continue Our Legacy of Heroism

Teach our children to continue Our Legacy of Heroism

Personal Account: ERIE MAESTRO

I live in Vancouver for now. Nanay ni (mother of) Inday Lara.

I am a Librarian and archivist; University of the Philippines alumnus, continued on to get my MLIS from Dalhousie University (Halifax, N.S.) and MAS from the University of British Columbia.

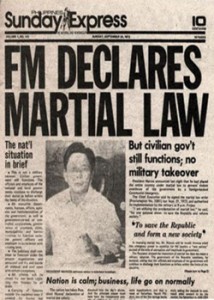

I was a student at the University of the Philippines when Martial Law was declared in 1972. I had enrolled at Maryknoll College for my first year in college, a decision that I regretted– I passed the UPCAT and could have started in UP right away but didn’t. In 1971, the Marcos government suspended the writ of habeas corpus which was a grim foreboding of more repressive measures to come. I remember one of the college seniors running along the corridor in Maryknoll, shouting that the writ had been suspended and basically asking that we should be concerned. I was a young freshman then and was struck by the seeming apathy of the other college girls. I decided then that I had to get out of Maryknoll fast and I did! I went to UP in 1972 and knew immediately that this was where I belonged.

No one at that time could have missed the huge student demonstrations, peasant pickets at Agrifina Circle, and jeepney strikes; no one could have missed the police brutality and state fascism that was the standard government response. It was on television and radio. It was the storm that took the Philippines and came to be known as the First Quarter Storm.

As a fourth year high school student, I tagged along with my eldest sister to a farmers’ picket at the Agrifina Circle in the early 70s and this made a deep impact on my sense of justice and politcal involvement.

So it was the height of the nationalist movement when in 1972, I finally transferred to UP and joined Gintong Silahis (GS), the cultural arm of a national democratic mass organization called the Samahan ng Demokratikong Kabataan (SDK). I met a lot of cultural activists who sang, recited poetry, and performed on stage and in the most unlikely places – picket lines, streets, demonstrations. I had only been a member for a couple of months when Martial Law was declared in September. School was out for awhile. The GS, along with other organizations, was banned and considered by the government as illegal and subversive.

I was not arrested during Martial Law. But a lot of my friends and schoolmates were. The Gintong Silahis members who were performing in Northern Luzon did not know that ML had been declared and they were one of the first political detainees in the country. Many young men and women who were arrested and detained kept up with their involvement in the resistance when they were released. One of them was a GS member, Leah Masajo, who could recite Amado Hernandez’s Kung Tuyo na ang Luha mo, Aking Bayan better than anybody else. She was killed by government troops in 1976 in Mauban, Quezon. It would take a while for her family and friends to retrieve her body for a proper burial. I later learned that Leah was pregnant when she was killed. To honour Leah’s memory and her role in history, I named my child after her.

Martial rule tried to eliminate dissent but failed miserably. While the Marcos dictatorship outlawed all pre-martial law activist formations and organizations, the people’s movement /the national democratic movement continued to stretch the limits of martial rule; the sectoral organizations grew and bloomed where the people were. Demonstrations, “lightning rallies” public and student protests were back. Cultural presentations were sharp, hard-hitting and popular. The military responded with fire trucks, water hoses with dye- colored water, truncheons, surveillance, arrest and detention, etc. In UP, I became active in the cultural sector and it was in the cultural work in UP that I met Marco Palo, who would later become my husband and later, my ex-husband.

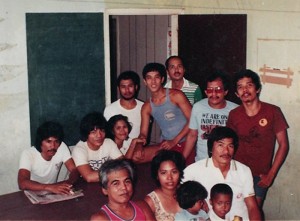

Inside the Bicutan Rehabilitation Centre, seated in front: Front row L-R: Rene Marciano, Rebecca Tulalian with the two children, Satur Ocampo. Back L-R: Alfredo Mansos, Edwin Lopez, Erie Maestro, Rolando Salutin, Marco Palo, Sixto Carlos, Bal Pinguel and Noel Etabag [1983]

The official “lifting of martial law” in 1981 was belied by the presence of political prisoners, the continuing arrest and detention of activists, massacres in the countryside, violence at the picket lines, militarization and internal displacement, abductions and forced disappearances, etc. No one in their right minds believed that martial rule was over. When my husband was arrested, the Marcos dictatorship made everything so much more personal to my family and in-laws. And with Marco’s arrest, both our families’ support and involvement in the struggle against the dictatorship, against imperialism and state fascism began, if not made stronger.

My husband Marco Palo was arrested in February 1982 with other labour organizers; the military conducted several raids from February to March and rounded up 23 men and women. They were church people, trade union organizers, peasant organizers, workers and activists. All were tortured. During the time that the military kept on denying my husband was in the Camp Crame, they were torturing and interrogating him.

Torture

When his family and mine were finally allowed to see him, he was very weak and could hardly stand up; we insisted several times that he get medical treatment. The miltary was forced to rush him to a military hospital where he stayed for several days. It was at this time that I saw the marks on his body, which I later learned were burns from electrocution. He was later transferred to V. Luna Hospital where Dra. Mamita Pardo de Tavera of the Medical Acton Group was able to visit and examine him until he was finally transferred to the Bicutan detention centre where the other political prisoners were detained. In his affidavit, he described his arrest, torture, interrogation and denial of his civil, political and human rights at the hands of the military.

On February 1983, Marco and the 22 other co-accused in the subversion case filed an unprecedented civil suit for P6.5 million in damages against then AFP Chief of Staff Gen. Fabian Ver and other military officials that included Col. Rolando Abadilla, and Lt. Cols. Rodolfo Aguinaldo and Panfilo Lacson for violating their human and constitutional rights. In July 1983, these same detainees also filed a formal complaint with the UN Human Rights Commission and asked for a formal investigation into their case because they had exhausted all possible means to attain redress under Philippine laws. These were detainees’ fighting back in the many ways that they could. Indeed, prison walls do not prevent the detainees from continuing to organize and struggle for their rights and freedom.

Detainees Fight Back

In the history of political detention in the Philippines, the detainees fight back through many ways which include – petitions and statements, dialogues with the military and prison authorities, to the wearing of black bands and the unfurling banners of “Free ALL Political Prisoners” when they are escorted to their hearings, to the filing of counter-charges against the government and the military. The weapons of the prison hunger strike and the protest fast are wielded when all else fails. We witnessed these prison struggles as relatives; any prison actions were supported with campaigns and support actions outside of prison by the families and friends of the political detainees.

My husband was released after two years. During those two years of his detention, I was consumed with working for his release, like any other family member of any political detainee. I had no choice but to quit my teaching position at a private high school. I became a member of KAPATID, the organization of the relatives and friends of political detainees. I later became a human rights worker with the church-based human rights office Task Force Detainees of the Philippines. In 1983, shortly after the assassination of Ninoy Aquino, I was given the chance to go to New York to represent the relatives of the political prisoners at the church sponsored conference at Stony Point. There was a shift in the political mood and I felt that this was the beginning of the end of the dictatorship.

Detention takes its toll on many families and many relationships, including mine. Our relationship was over at the end of 1984. My ex-husband was arrested again under the Cory Aquino government in the 1988, detained in Camp Crame and was subsequently released after a year or so.

Wonderful People

In the midst of this difficult period, I also met the most wonderful people from many different sectors. My newfound extended family included other mothers like Ka Osang Beltran and Mommy de la Torre, lawyers like Ka Pepe Diokno and Arno Sanidad, brave nuns in the likes of Sisters Mariani, Bernard, Bobby, Mary and Salud and journalists (Jo-ann Maglipon became a close friend), the other wives, among them Seling, Ecca, Ka Mila Buscayno, Connie and their children and, of course, the many political prisoners both in the regular detention centres as well as in the National Penitentiary in Muntinglupa. In the most desperate of times, the humor and laughter, the patience, the courage of these people lifted me through the hard times. I would like to think that regardless of changes in circumstances and political lines, the bonds and relationships with these friends remain strong and respectful.

Issue of Political Prisoners

The issue of political prisoners holds a special soft spot in my heart. Political prisoners are the living witnesses to the repression and fascism by the State. “Free All Political Prisoners” still remains as the rallying call for the over 300 political prisoners scattered in different camps, jails and detention centres.

In Canada, so many years after and so many miles away from home, working with the Canada Philippines Solidarity for Human Rights (CPSHR) is the opportunity to work for the release of political prisoners, find justice for the “missing” and those killed by the government and the military. Post-Marcos governments have continued to kill, maim, abduct and forcibly disappear, torture and detain those critical to their policies and actions. And post- Marcos governments, including this present one, continue to confront a people’s movement that is growing and expanding because the objective conditions of poverty, neo-colonial dependence, landlessness, hunger and injustice still exist.

Serve the People

Someone once said that terrible things continue to happen not because of bad people but because of good people who do nothing. It is oftentimes too easy to turn a blind eye to what is happening in the Philippines, to forget that to have studied and graduated from UP as a “iskolar ng bayan carries a legacy and responsibility to yes, serve the people in whatever way we can.

The lessons are never to forget what we as a people have suffered through. To always remember that our freedoms are fragile. To remember that as a people, we come from a lineage of strong heroic men and women throughout our history who fought on all fronts and put their lives on the line for democracy and freedom. To teach our children to be proud of who they are and their history and to continue the legacy of those who fought and were imprisoned, especially during the dark periods of our history.

Comments (0)