Stories from a political prisoner

Stories from a political prisoner

INTERVIEW WITH ANGIE IPONG

In a book recently launched in Toronto, a former political prisoner is speaking out about her years in jail under false charges following decades of advocacy for indigenous and farmer rights.

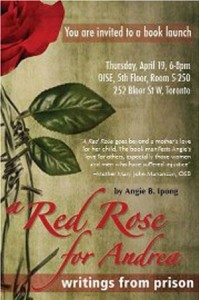

Angie Ipong spoke about her book, A Red Rose for Andrea, to over fifty people at the book launch at OISE on the University of Toronto campus on April 19. The book recounts stories from her imprisonment on charges that were dropped after six years. Until her release last year, Ipong was the oldest woman political prisoner in the Philippines.

There are nearly 350 political prisoners in the country. Human rights groups say the perpetrators are private and state-sponsored militia who operate without punishment or accountability.

Ipong is the secretary general of Samahan ng mga Ex-Detainees Laban sa Detensyon at Aresto (SELDA). The proceeds of A Red Rose for Andrea will support political prisoners in the Philippines.

Ipong recently spoke to The Philippine Reporter about her arrest, imprisonment, new book, and North American tour speaking out against the culture of impunity in the Philippines.

Q. What did you do before being arrested?

A. For many years I worked with the farmers and indigenous people in Mindanao. In the 1970s, I worked with farmers in the banana plantations because at the time they were encroaching on the land of the peasants. Since that time, I worked in advocacy for farmers and peasants rights, alongside rural missionaries and churches.

Q. What happened during your arrest?

A. I was arrested on March 8, 2005. We were having a meeting of women peasant leaders and they abducted me. They dragged me into a van and immediately blindfolded me. They brought me from camp to camp. They continuously interrogated me. I could not sleep for those four nights.

Later, they took me via helicopter to another camp and I was incommunicado for 12 days with no right to legal counsel. I was beaten in my head, struck in my shoulders and my hips.

The worst thing they did to me was undress me and start to touch my private parts. I said, “No, no! Don’t do this to me! Don’t do what you wouldn’t want done to your mothers and your sisters.” But they were laughing at me with mockery and indecent words. I couldn’t believe that such a thing could happen to a 60-year-old woman like me.

Q. Then you went on a hunger strike?

A. Yes. When I was in that state, I had the fear of the unknown and later the fear of death. But as soon as I accepted these things, I started to get bolder. After 12 days, I think they heard what I said during my protest act because they brought me to a regular detention centre.

Q. Where were you before that?

A. It was a secret detention centre. I think it was a torture chamber because there was a big life-sized mirror that covered the whole length of the wall. There was a microphone protruding. On the other side, there was a big chain for people to be chained. There were only two chairs and a table.

I was the only one there and only those torturers would come in, in different groups. After I was tortured, they left me and turned on the air-conditioner full blast. I was so cold. It was terrible the ordeal I experienced under these military men.

Q. What was it like in the jail?

A. After so many days, my head was aching, my body was in pain, my blood pressure was rising and my extremities were numb. I asked the warden if I could stay in the chapel so I could get some fresh air. There, I thought maybe I could do some gardening in a space in the prison compound. I was permitted and started to work.

As I worked, I found my health was improving. After two to three months we had a big organic garden. The other inmates also helped and the garden became a way to bond. We would make salad every morning and give it to my co-inmates and guards, and sell the vegetables. We also started to sew clothes and cook, and of course we fought for our rights in jail.

This was in the Pagadian City Jail in Zamboanga del Sur. After four years and seven months I was transferred to another jail.

Q. What was it like there?

A. I thought, “What will I do here?” There was no place to garden. There were many political prisoners there. In the previous jail, I was the only one.

Then I found they did not separate the biodegradable and non-biodegradable garbage. So we made the biodegradable garbage into compost. Because the space was small, we started to plant in pots and plastic bags and made hanging gardens, and this jail also became green. The prisoners were happy because it became a way to have healthy food.

Q. Where did you get the stories for your book, A Red Rose for Andrea?

A. These are stories of the political prisoners in the second jail. They’re stories of their lives, the situation that brought them into jail, the torture that they experienced, and the different things that we did in jail to cope. We talked about the things that we did to make changes, despite the prison walls and iron bars.

Prison walls and barbed wires could only imprison our bodies, but not our hearts and our minds and what we stand for. Wherever we are, if stand for our rights, we will always find strength.

Q. The other political prisoners shared stories with you and you wrote about them?

A. Yes. We had a journalist with us in prison and we interviewed our comrades there. Even the non-political prisoners also wanted to tell their stories. So every now and then we would interview people and ask someone who was visiting us to type them.

When I was released from jail in 2011, that’s when we edited them and put them together. So the book tells these stories, and also what our justice system is all about– the prison institution as a coercive instrument of the state.

Q. There was a lot of concern for your safety at the book launch.

A. Yes, many of people have told me that already. But I say, “When else and who else can tell these stories?” We have the experience and have the responsibility to tell people.

That’s why I told the people at the book launch, that if ever something happens, you are there to help.

Q. Tell me about the experience sharing your story throughout North America.

A. They were very interested in my story. Some of them did not know these things were happening, even the Filipinos. They thought the Philippines is now a democracy; they have a new government. But when they hear us, they say, “Oh it’s still happening?”

Many communities were interested in doing something, but the question is how?

There are 347 political prisoners. We can work for their release by signing petitions and letters to the President and the Department of Justice. We can adopt prisoners, write to them, and help their families, like help their children go to school. The call to end these killings, to stop this impunity is very important.

(The interview was edited and condensed.)

Angie Ipong’s ‘A Red Rose for Andrea’ Book Launch

Angie Ipong (3rd from left) with sisters Martha Ocampo (2nd from left) and Fe Grzcinc (right) and nieces Natasha and Sarah.

PHOTOS: HG

Comments (0)