The Scribe, the Slave and the Screwups

The Scribe, the Slave and the Screwups

Book cover of Antonio Pigafetta’s book

By Michelle Chermaine Ramos

The Philippine Reporter

As the Philippines celebrates 500 years of Christianity you might see historical paintings online romanticizing the first baptism in the Philippines of Rajah Humabon of Cebu and his subjects initiated by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan.

While the Spanish explorers would claim credit for evangelizing the island heathens, their motives have always been far from altruistic and deliberately profit and power-driven as seen from Magellan’s selective diplomacy and meddling in local politics recorded in Antonio Pigaffeta’s diary. Pigafetta was an Italian explorer from a prominent noble Vicentine family who joined Magellan’s expedition in 1519 sponsored by Spain. Pigafetta shares his riveting first-hand account in his book, The First Voyage Around the World 1519-1522, from The Lorenzo Da Ponte Italian Library edited by Romance Language Professor Theodore J. Cachey Jr. for the University of Toronto Press.

He was an observant ethnographer who recorded what he witnessed in detail, painting us a colorful picture of how precolonial Filipinos lived including his translations of some words in their language, and his notes on their native beliefs, cuisine, clothing, lifestyle and the islands’ natural resources. There is a wealth of information in this book, but for this article, we will focus on some fascinating facts leading up to and after the battle of Mactan.

Our ancestors were loaded with gold

The foreigners were thrilled to discover the abundance of gold as Pigafetta wrote of Rajah Colambu’s territory of Butuan and Caraga, “Pieces of gold the size of walnuts and eggs are found by sifting the earth in the island of that king who came to our ships. All the dishes of that king are of gold and also some portion of his house, as the king himself told us.” He also noted that he “had three spots of gold on every tooth, and his teeth appeared as if bound with gold”. No doubt this served as an incentive for Magellan to befriend him and his brother Rajah Siaiu.

Ferdinand Magellan, Portuguese explorer known to have “discovered” the Philippines in 1521.

Magellan created political tension using religion as a tool

To impress his new friends, Magellan asked Rajah Colambu “to declare whether he had any enemies, so that he might go with his ships to destroy them”. He merely thanked Magellan and said that there were two islands hostile to him, but it was not the reason to go there. Records of their interactions with the natives show Magellan’s inconsistent approach to convert different tribes. Some he told should convert not merely out of fear or to please them, but out of their own free wills, while others he threatened to massacre if they refused. When Magellan befriended Rajah Humabon of Cebu and convinced him to convert to Catholicism and the chiefs under him refused to obey, Magellan threatened to kill them and give their possessions to Rajah Humabon. Magellan then promised to make Rajah Humabon the greatest king in those regions (subject of course, to the king of Spain). Before the week of April 14, 1521, was over, they baptized his subjects and people from some neighboring islands.

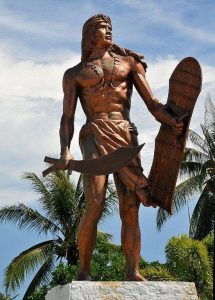

Magellan and Lapulapu had bad blood even before the battle of Mactan

Contrary to the assumption that Magellan was simply an unfortunate explorer viciously murdered upon landing by hostile savages led by Chief Lapulapu (Cilapulapu), Pigafetta tells a clearer tale. The week the Spanish baptized people of other islands subjecting them to Rajah Humabon’s rule, they burned a village named Bulaia on Lapulapu’s territory for refusing to convert and give them tribute. On Friday, April 26, 1521, Chief Zula, another chief on the island of Mactan, reported that Chief Lapulapu refused to obey the king of Spain and prevented him from sending all the tribute he promised Magellan. Learning this, Magellan agreed to help him conquer Lapulapu’s territory. “We begged him repeatedly not to go, but he, like a good shepherd, refused to abandon his flock,” wrote Pigafetta.

Lapulapu’s statue in Cebu.

He and his group resisted Spanish colonialism and

defeated Magellan’s

invading forces.

At midnight, Magellan set out with his armed Spanish soldiers and Rajah Humabon’s forces of “twenty or thirty balanghai (large boats)” and reached Mactan three hours before dawn. Pigafetta reports Magellan sent a message saying, “if they would obey the king of Spain, recognize the Christian king (Rajah Humabon) as their sovereign, and pay us our tribute, he would be their friend; but that if they wished otherwise, they would expect to see how our lances wounded.” Lapulapu simply replied along the lines of, “Well, we got lances of our own. See you in the morning!”

Magellan’s deadliest mistakes

In yet another arrogant attempt to flex in front of Rajah Humabon, Magellan told him and his forces to stay on their balanghai and simply watch how he and his forty-nine men (including Pigafetta) fought. Magellan overconfidently believed that one armed Spanish soldier could defeat one hundred native warriors. He failed to consider the rocks in the water. They had to leave the ships and wade in thigh-deep water more than two crossbow flights to reach the shore where over 1,500 natives swarmed on them. Their musketeers and crossbowmen uselessly shot from a distance and ran out of ammunition. Neither could the mortars on the Spanish ships help them so far away. Four natives of Rajah Humabon’s forces who left the boats to aid them were accidentally killed by the mortars. Rajah Humabon was placed in the embarrassing position of having to send a message negotiating with the people of Mactan to trade the bodies of Magellan and the other fallen men for all the merchandise they wanted. Not for all the riches in the world was their reply.

Magellan’s Filipino slave and his successors’ biggest blunder

Enrique, Magellan’s faithful slave, who had accompanied him on his previous voyage and acted as his interpreter between the Filipino kings, was wounded in the battle of Mactan. It was Magellan’s will for Enrique to be set free upon his death but the two commanders who replaced Magellan, namely his relative, Duarte Barbosa and Spaniard, Joao Serrao, refused to set Enrique free. Instead, Barbosa told him that he would be brought back to Spain to serve as Magellan’s widow’s slave. He also threatened to flog him if he refused to go ashore to Rajah Humabon’s island to tell him they were leaving soon. Enrique complied and returned to the ship.

On May 1, 1521, Rajah Humabon said that the jewels he prepared for the king of Spain were ready and he invited the commanders and their companions to what turned out to be deadly despedida. Twenty-four men joined the banquet. Pigafetta was unable to attend as he was recovering from a forehead wound from a poisoned arrow. Two men returned to the ship on a bad hunch. No sooner had they shared their apprehensions when they heard loud cries from the island. They saw Joao Serrao on the shore bound and wounded begging to be rescued saying all were slaughtered except for Enrique. Ignoring his pleas for help, the ships immediately departed and eventually made their way to the island of Bohol.

Pages of the book of Pigafetta showing drawings of islands of Bohol, Cebu and Mactan.

——————————

Michelle Chermaine Ramos is a multidisciplinary artist and multimedia journalist focusing on arts, culture, spirituality, martial arts and news that impact Filipino Canadians. She has profiled prominent entrepreneurs and trailblazers in the diaspora. E-mail: pitchmichelle@gmail.com for news tips or book recommendations.

Michelle Chermaine Ramos is a multidisciplinary artist and multimedia journalist focusing on arts, culture, spirituality, martial arts and news that impact Filipino Canadians. She has profiled prominent entrepreneurs and trailblazers in the diaspora. E-mail: pitchmichelle@gmail.com for news tips or book recommendations.

Comments (0)