‘Better dead than read’: The years of writing dangerously

‘Better dead than read’: The years of writing dangerously

September 12, 2022

Ma. Ceres P. Doyo

By Ma. Ceres P. Doyo

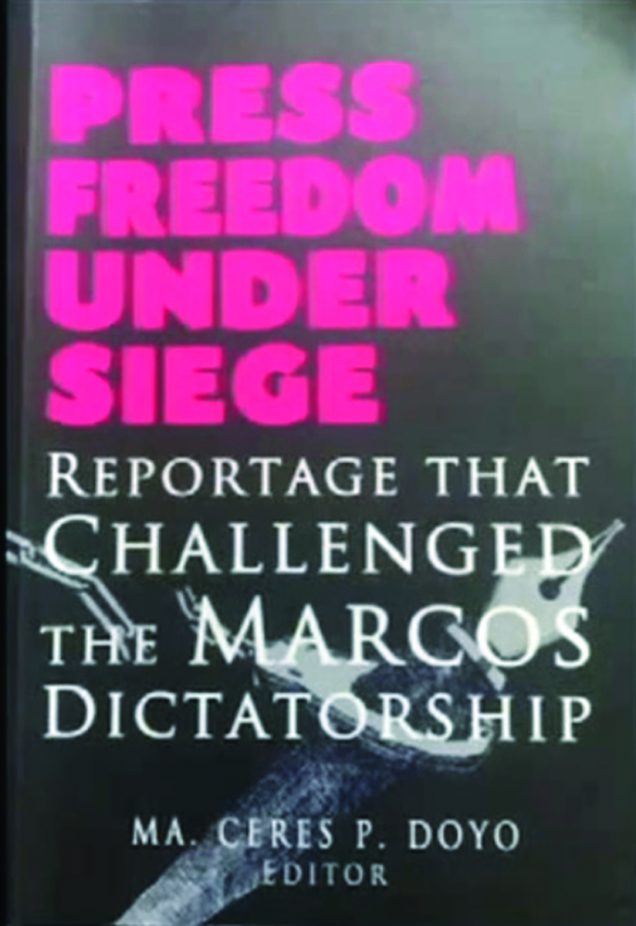

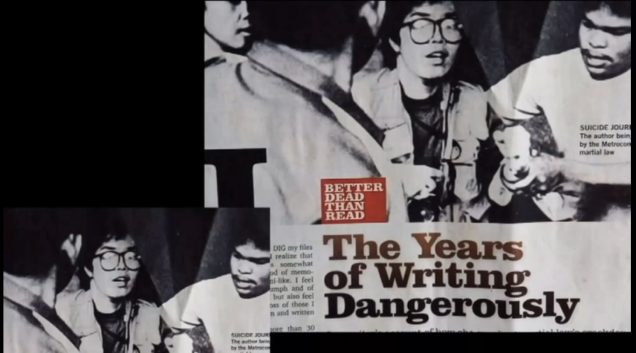

Good evening, good morning to all who are here. Although this gathering is about my book “Press Freedom Under Siege: Reportage that Challenged the Marcos Dictatorship,” the title of this talk is “The Years of Writing Dangerously.” (Flash screen shot of “The Years of Writing Dangerously and let it stay for some seconds.) That is me being dragged by the dreaded Metrocom at a rally. But I got away!

After I accepted this invitation to speak before you, I realized that this could be discomfiting like other invitations of this nature. My heart was skipping beats while I was writing down my thoughts. A flood of memories surged, tsunami-like. I felt the warmth of triumph and of freedom long-won, but I also felt sadness over the loss of those I had met and known and written about.

Somewhere, it all began. Let me begin with the personal.

Somewhere, it all began. Let me begin with the personal.

On July 10, 1980, my face was on the front page of the Bulletin Today, the biggest newspaper in the Philippines at that time. The photo caption read: “Hearing: A magazine writer, Ma. Ceres Doyo, answers questions from Deputy Defense Minister Carmelo Barbero, chairman of the Armed Forces human rights committee, in connection with her article on the death of Bugnay chieftain Macliing.” The caption was misleading. It was not a “hearing,” it was a public interrogation. Human rights committee? Really!

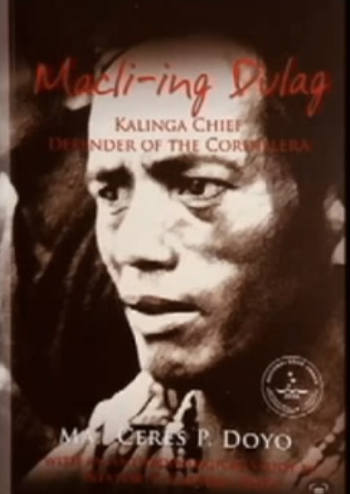

The article headline was simply, “MACLI-ING.” All caps. The blurb was also misleading: “Dismiss link between dam, tribesman slay.”

Several other national newspapers carried the story on my interrogation because of my Maclling Dulag story which came out in the Panorama Magazine dated June 29, 1980. The story about Macli-ing’s murder and the investigations refused to die. It ran for days in the Marcos-controlled newspapers and in two foreign magazines. Letters to the editor and to me poured in.

By the way, my book on Macliing Dulag won the National Book Award for Journalism in 2016.

As a writer, that Camp Aguinaldo interrogation was my first high-profile brush with the military. (A few years earlier, writer Chit Estella and I were seized by the Metrocom while we were transporting an anti-dictatorship publication, “Iron Hand, Velvet Glove,” for a church-based human rights group. It was night and I was driving a car full of “subversive” materials. The armed men released us upon the intercession of Sr. Mary Christine Tan RGS and Fr. Ralph Salazar who now dwell in the eternal hills.)

As a writer, that Camp Aguinaldo interrogation was my first high-profile brush with the military. (A few years earlier, writer Chit Estella and I were seized by the Metrocom while we were transporting an anti-dictatorship publication, “Iron Hand, Velvet Glove,” for a church-based human rights group. It was night and I was driving a car full of “subversive” materials. The armed men released us upon the intercession of Sr. Mary Christine Tan RGS and Fr. Ralph Salazar who now dwell in the eternal hills.)

(For the Macli-ing story I received the summons, dated July 5, 1980, through Panorama editor Letty J. Magsanoc (who would later be the Inquirer editor in chief). She, without batting an eyelash, published my story about the killing of Macli-ing Dulag, chief of the Butbut tribe in Kalinga-Apayao. She sure gave it a provocative title: “Was Macli-ing killed because he damned the Chico Dam?” Macli-ing led his tribe in opposing the construction of the Chico River dam. One night, military men barged into his mountain home and pumped bullets into him.

With a group of church and human rights workers I went to Kalinga on a fact-finding mission. To get to Bugnay village we scaled hills and braved crossing the raging Chico River with the help of Kalinga braves in G-strings. In the home of Macli-ing I saw the blood on the wall and ran my fingers on it. I listened to the people’s stories and took photographs. After that I don’t know what possessed me but I just sat down and wrote. I sent the story and trembled, trembled. A dam inside me had burst.

That was my first major feature article and I got the editor and myself in trouble. Oh yes, before going to the interrogation I went to Sen. Jovito Salonga, a former martial law jailbird. His advice: “Go.” He said it like a blessing. A horde of nuns and a very concerned aunt of mine came with me to the interrogation. They took down notes–the questions, my answers. The transcript of that interrogation is in my book “Press Freedom Under Siege” which is the focus of our sharing session today.

A few months later, in January 1981, Pope John Paul II came for a blockbuster visit. What do you know, he handed me the Catholic Mass Media Awards trophy for that Macli-ing story. He held my head with both palms. It was never the same after that. The writing continued. My editor Magsanoc would call it “suicide journalism.”

A few months later, in January 1981, Pope John Paul II came for a blockbuster visit. What do you know, he handed me the Catholic Mass Media Awards trophy for that Macli-ing story. He held my head with both palms. It was never the same after that. The writing continued. My editor Magsanoc would call it “suicide journalism.”

The second interrogation was in 1983. There was this series of summons for and interrogations of women writers that went on for several days. This time, the individual interrogations were inside closed doors and the interrogators were high-ranking military officials—a general and several colonels (one of them a woman). There was food galore—and wine, too—but how could one eat while being cracked?

I was the first to be summoned to Fort Bonifacio. Next were Domini Torrevillas, Jo-Anne Maglipon, Lorna Kalaw-Tirol, Ninez Cacho-Olivares, Eugenia Apostol and Doris Nuyda. Torrevillas, Coronel, Tirol and I (a freelance writer at that time) were writing for Panorama, the Sunday magazine of Bulletin Today. Olivares and Babst were Bulletin columnists. Apostol was the publisher and Nuyda an editor of Mr.&Ms. magazine. Obviously, the military and, it goes without saying, the dictatorship did not like what we were writing. (A footnote: The Inquirer, begun in December 1985, was not yet a gleam in the eye of Eggie Apostol.)

For several hours the military officers questioned me for my magazine stories on the military’s human rights abuses in Bataan and rebel-priest Fr. Zacarias Agatep who was killed in an encounter with soldiers. The Macli-ing story was also brought up. I was giving the government a bad image, I was told. Oh, but before the interrogation began, I, with pen and paper and with an air of defiance, said loudly: “Please give me your names.” And they did.

For several hours the military officers questioned me for my magazine stories on the military’s human rights abuses in Bataan and rebel-priest Fr. Zacarias Agatep who was killed in an encounter with soldiers. The Macli-ing story was also brought up. I was giving the government a bad image, I was told. Oh, but before the interrogation began, I, with pen and paper and with an air of defiance, said loudly: “Please give me your names.” And they did.

We all emerged uncracked. Ah, the stories we narrated to one another. What did we—the women writers—do next? Having gotten all the interrogators’ names, we plotted in the dead of night and built a case against them with the help of the Flag and Mabini lawyers. We strode into a jam-packed Supreme Court to question the so-called National Intelligence Board, a creation of the military dictatorship to cow writers. We won! The respondents said they were done with it anyway. Duh. We were front-page news.

Not long after, Panorama editor Torrevillas and I were each slapped a P10-million libel suit for my Bataan military abuses story. Courtesy of a military general who was not even in Bataan at that time, I was told. Poor guy. Nautusan lang.

My lawyers: Saklolo Leano (Siguion-Reyna Law Offices), Flag and Mabini lawyers Joker Arroyo, Rene Saguisag, Fulgencio Factoran, Jejomar Binay, Antonio Rosales, Augusto Sanchez, Lorenzo Tanada. The same ones who marched with us to the Supreme Court. At the preliminary investigation Arroyo and Saguisag exchanged barbs with the fiscal nicknamed Joe Flame (Jose Flaminiano) who proceeded to file the case because he had to. (The case was dropped after the People Power uprising and Cory Aquino rose to the presidency.)

My lawyers: Saklolo Leano (Siguion-Reyna Law Offices), Flag and Mabini lawyers Joker Arroyo, Rene Saguisag, Fulgencio Factoran, Jejomar Binay, Antonio Rosales, Augusto Sanchez, Lorenzo Tanada. The same ones who marched with us to the Supreme Court. At the preliminary investigation Arroyo and Saguisag exchanged barbs with the fiscal nicknamed Joe Flame (Jose Flaminiano) who proceeded to file the case because he had to. (The case was dropped after the People Power uprising and Cory Aquino rose to the presidency.)

But there were other writers and stories that suffered but were not widely known and documented. So in 1984 and 1985, a group of us came up with two volumes—“The Philippine Press Under Siege”, volumes 1 and 2, that contained “dangerous writing,” stories that provoked the Those two small volumes of limited circulation edited by Leonor Aureus were the parents of this big book that we are launching now. This offspring, this present one-volume PFUS, was published by the University of the Philippines Press in 2019. It is a redesigned, re-edited version and with added pieces to make it more comprehensive. The UP Press is now preparing a 2nd edition because the 1st has run out. This book recently won the National Book Award in the Journalism. Category.

From the previous editors’ notes: “Together, (these stories) show the kind of ‘dangerous writing’ that has brought about the forced resignation, firing, blacklisting, arrest or detention of journalists, the padlocking or sequestering of a newspaper’s printing plant and equipment, and the filing of multi-million peso libel suits or subversive charges against writers, editors and publishers.

“What constitutes ‘dangerous writing’ these days? Perhaps this volume can shed some light on this question. Two articles…deal with the President (Marcos Sr.) Six are on the growing militarization in the countryside. Two are about election fraud and two on the aftermath of the Aquino assassination.”

National Club president Tony Nieva wrote then: “Better dead than read” may well have been the title of this book for its graphic documentation of the blood-and-sand state of a profession under siege, underlying the personal struggles and heartbreaks of the men and women of the Philippine press who now work under the shadow of death itself.”

National Club president Tony Nieva wrote then: “Better dead than read” may well have been the title of this book for its graphic documentation of the blood-and-sand state of a profession under siege, underlying the personal struggles and heartbreaks of the men and women of the Philippine press who now work under the shadow of death itself.”

Fast forward years later. I was one of the almost 10,000 individuals who filed a class suit in a Hawaii court against Ferdinand Marcos and his estate—and won. The claimants were awarded $2 billion. In 2010, almost 25 years after the dictator’s downfall, the victims and survivors of martial law excesses finally got trickles in the initial amount of $2,000 or so each from discovered hidden/ill-gotten stash. We know there’s more where this came from and the claimants have not yet been fully compensated. You may ask questions on this later.

It was a measly sum for all the blood—and ink, in our case—that was poured, until and unless the other claimant, the Philippine government looks the other way.

Oh yes, separately, repeat, separately, through R.A. 10368 signed by Pres. Noynoy Aquino, 11,103 claimants received their remuneration from the P10 billion which the Swiss government returned. This is different from the one won in the Hawaii Court.

I hope you can watch the documentary “11,103” that will be premiered soon. There will be a premiere showing in the US.

And now for the book we are launching virtually in cyberspace today in this part of the planet.

Like I said earlier, those were years of writing dangerously, we would say. But, for a good few, fearless writing never really stopped completely during those dangerous times, though much of it done sub-rosa or in the so-called “mosquito press” sometimes called alternative or underground press. And when that brand of “subversive” writing finally broke into the open, it did so with daring and defiance. Like a swollen river raging to break free, like a boiling sea smashing against boulders. Like a mother in the throes of childbirth, writhing, screaming in pain in order to bring new life.

That was how it was in the 1980s, during the waning years of the Marcos dictatorship, though waning would hardly be the applicable word at that time because it did not feel that way; because the dictator’s iron hand still had a tight grip on the media and the entire nation, years marked by with tyranny, repression, and oppression.

This book, this compilation, is a testament to the courage and outrage of the writers who dared, defied, and exposed, through the written word, the excesses of the fourteen-year-long dictatorial rule (1972–1986) of Ferdinand E. Marcos and his family, his government, and trusted men, the military institution in particular, that carried out the unspeakable cruelty against a terrified people and those who dared to fight back.

This book is for both journalists and non-journalists, also for lovers and practitioners of law especially where freedom of the press is concerned. (Lawyers can look into the appendices.) This book is for the present and future generations, for them to appreciate the power of the written word and the importance of keeping watch in the night with their lamps trimmed while the battle rages between darkness and light.

The reader need not seethe or rage with the writers as if caught in a time warp; they can now read these pieces with equanimity, even enjoy some of them as they would a movie or whodunit. But not to forget that cinematic as some stories may appear, they were for real—the events, the characters, the storytellers, the heroes, and the villains. Almost all the articles in this book exposed the tyrannical climate of martial rule that hovered on the benighted nation, the excesses and abuses that victimized countless individuals and communities, the lies and coercive bend that characterized those in power who ruled roughshod with impunity.

But just as riveting as the bylined stories are the consequences—described after every article or in whole chapters—that befell the persons behind the bylines, the authors who bore the consequences of the words they wrote and who bravely faced their tormentors. Media shutdown, arrests, detention, forced resignations, interrogation, libel (“scurrilous!”) cases, threats—and death for some—were the lot of many writers and their publishers during the Martial Law years.

But the stories in this book are those mostly written in the 1980s when emboldened journalists, mostly women, rose to wield and wave the pen against the dictatorship. Read about the murder by the military of Kalinga chief Macli-ing Dulag, the plight of the Atas of Mindanao (flash the p. 61), the Las Navas massacre, the killing of a country doctor. Read about the fake war medals of the dictator Marcos that resulted in the raid of We Forum published by Joe Burgos.

Read the pieces that exposed and challenged the conjugal dictatorship, its excesses and the ways and means it employed to cow, silence, threaten, terrorize, and eliminate those who did not pay allegiance to the so-called New Society. Read the interview about the assassination of Ninoy Aquino that resulted in a monumental libel suit against Mauro Avena.

Learn about the aftermath of the writers’ boldness, how the dictatorship and its minions tried to intimidate them—through arrest and detention, threats and surveillance, interrogations, forced resignations, multimillion libel suits, etc.—to hush them up and make them pay for their daring.

Read the pieces by Letty Jimenez Magsanoc, Jo-Ann Q. Maglipon, Sheila S. Coronel, Ma. Ceres P. Doyo, Rene O. Villanueva, Arlene Babst, Mauro Avena, Chelo Banal, Domini Torrevillas, Lorna Kalaw Tirol, Ninez Cacho Olivares, Leonor Aureus Briscoe, Sylvia Mayuga, Recah Trinidad, Roberto Z. Coloma, Melinda Q. de Jesus, Alex R. Magno, Alex Dacanay, et al., that appeared in various publications. Included in this volume are some articles that were banned and never saw print.

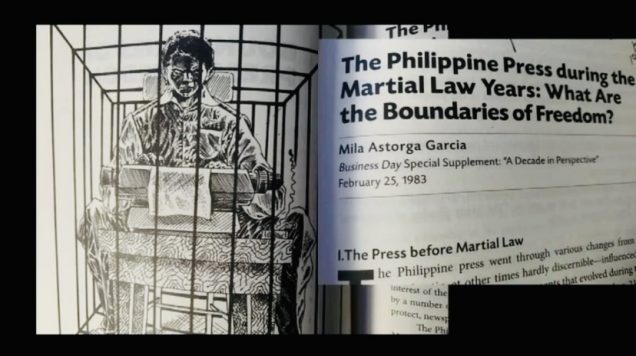

A well-researched piece by Mila Astorga Garcia the “promotor” of this event (flash p. 152 and 153 title) published in Business Day in 1985, not included in the previous collection, is now in this volume to provide historical context and a view of the state of press freedom and un-freedom before and after the imposition of martial law in 1972. Pieces written in the so-called mosquito/ alternative/underground press not included in this volume deserve praise and recognition because publishing them at all was just as risky, if not life-threatening.

A number of the writers of the pieces in this volume would admit that, at one time or another, they had also written for the underground “subversive” press because the mainstream media were in shackles, if not under threat. Still included in this volume are the non-journalistic pieces, some of the legal kind that gave context to the issue of press freedom and censorship at that time. Some of the authors risked censure and being censored but they exercised brinkmanship to convey their thoughts to challenge the despotic dispensation.

This new, single, and thicker volume is the resurrected, reformatted version of those two books published by the Committee to Protect Writers composed mostly of WOMEN members, and the National Press Club of the Philippines under then club president Antonio Ma. Nieva who was thrown in jail for “inciting to rebellion.”

Why “resurrected”? Because there is a need to bring back to life, if not keep alive, historical facts that have to do with the freedoms we presently enjoy. Because there is now a creeping culture of forgetfulness and silence even among victims who had gone through those dark times (too traumatic to recall or discuss?—but yes, indeed). And, on the part of the victimizers, to revise history.

Filipino journalists continue to be killed—since the dictatorship ended in 1986, the count has breached 200—while the killers walk free and with impunity. One cannot ignore the hovering new threats to press freedom, where these have been coming from, and the reasons why. Under the Duterte government from 2016 until the present, the media in various forms and platforms have had to contend with the proverbial sword of Damocles hovering above them. Threats—subtle and not subtle—against these institutions and against individual journalists are the new normal.

Using social media, the paid trolls, hackers, hecklers, bashers, and peddlers of false news try to subvert the truth and supplant professional news reporting in order to advance the agenda of their financiers in high places. All that even while the Freedom of Information Bill—its passage long overdue— was being being barred at all cost by legislators and their backers who fear its power once passed. For history’s sake, the urgent call now is to instill interest in the past among the young. They who do not know much—or were not made to know?—about the sufferings of their elders or had not read about those dark, painful years in the course of their studies because . . .

But not to assign blame at this point, only to resolve to make sure that history does not repeat itself, that history does not get rewritten or revised. That NEVER AGAIN will tyranny subdue this nation, that NEVER AGAIN will voices be silenced, that NEVER AGAIN will the hand that writes be stilled.

Comments (0)