Culture and the Arts: The continuing struggle for Philippine Independence

Culture and the Arts: The continuing struggle for Philippine Independence

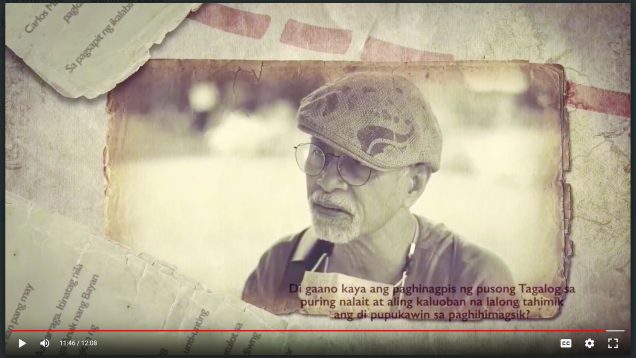

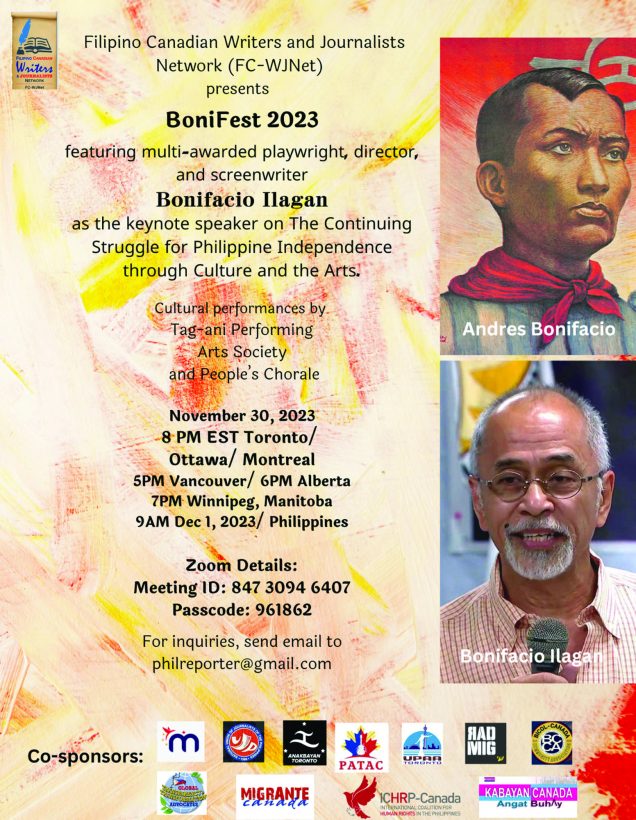

BONI ILAGAN

By Bonifacio P. Ilagan

Delivered via Zoom for the Andres Bonifacio Festival (Bonifest) 2023 in conjunction with Andres Bonifacio’s 160TH birth anniversary, sponsored by the Filipino-Canadian Writers and Journalists Network

Magandang araw at gabi sa ating lahat. Thank you for inviting me.

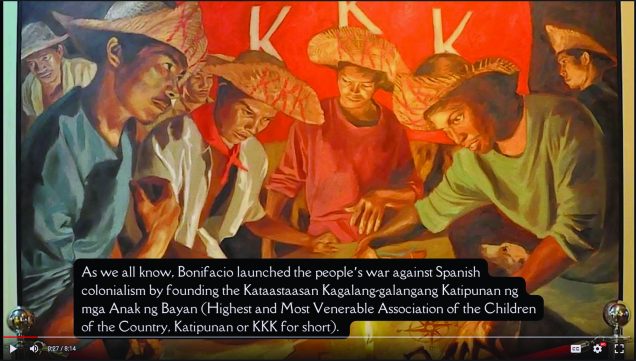

Nobody is asking, but I am telling. I was born on the same day that Andres Bonifacio, after whom this festival is called, was born 160 years ago. As we all know, he launched the people’s war against Spanish colonialism by founding the Kataastaasan Kagalang-galangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan (Highest and Most Venerable Association of the Children of the Country, Katipunan or KKK for short).

There’s another personal trivia I’d like to share with you. A younger sister of mine was born on the same day that the novelist and martyr Jose Rizal was born in 1861, thus her name Rizalina. If I did survive martial law, she did not. She was abducted by state security agents in 1977, the 5th year of the Marcos dictatorship, and has remained a desaparecida since then.

In the 1970s, my sister and I were cultural activists engaged in the movement for people’s art. She helped organize a chapter of the theater group Panday-Sining (Artsmith) in Southern Tagalog. I was the founding chair of Panday-Sining.

In the 1970s, my sister and I were cultural activists engaged in the movement for people’s art. She helped organize a chapter of the theater group Panday-Sining (Artsmith) in Southern Tagalog. I was the founding chair of Panday-Sining.

Question: Had Andres Bonifacio not been too preoccupied with the organizational issues of the underground movement that he started in 1892, and which eventually ended the 333 years of Spanish colonialism in the Philippines, could he have written more poems or pursued a theater career? It is little known that he once belonged to a theater group called Teatro Porvenir and acted in at least one play about the mythical Filipino hero named Bernardo Carpio. He also wrote the iconic poem “Pag-ibig sa Tinubuang Lupa (Love for the Native Land),” that had inspired composers and now considered an anthem by freedom-loving Filipinos.

I am glad that this years’s edition of Bonifest is taking up culture and the arts, which has been an integral part of our continuing struggle for Philippine independence.

Precisely owing to that struggle by Filipino freedom fighters, many of whom were artists like Andres Bonifacio, my generation inherited a tradition of resistance against foreign domination. That resistance had to be quashed, the new colonial masters who took over the Spaniards absolutely knew that. They also knew that armed force was never going to get the job of colonialism completed. They had to subjugate the minds and hearts of Filipinos as well. That is a question of culture. They needed to ensure that generations and generations of their colonial subjects would be nurtured after their image. It is interesting to know that the US invasionary troops in 1898 were also the first teachers who taught Filipino children how to read and write in American.

By the time that I entered grade school in the 1950s, American was no longer a strange language to me. By Grade 5, our curriculum included a course in US history and geography. I was tops in reciting from memory the names of the presidents as well as all the states and capital of the almighty union. Not to forget, we sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” by heart.

So what was wrong with that? What was wrong about living the American dream that was the land of milk and honey? Now, if we could not become US citizens, then we must at least acquire the stateside appliances and consumer goods that became the standard of the good life in a country whose people sang with misplaced nostagia about White Christmas when they only had the dry and wet seasons but felt satisfied that snow covered their Christmas trees, thanks to the illusion lent by medical cotton.

Here’s another personal trivia, if you may please indulge me. When my father reached 60, my whole family started receiving a pension from the US in our individual names because my father had lived in America for some 30 years. How generous Uncle Sam could be!

Here’s another personal trivia, if you may please indulge me. When my father reached 60, my whole family started receiving a pension from the US in our individual names because my father had lived in America for some 30 years. How generous Uncle Sam could be!

Entering the University of the Philippines in Diliman in 1969 and taking up a subject in Philippine history, I had to unlearn a lot of my childhood education and sentiments about the history of our country and Uncle Sam. I felt pain in the stories of the brutality and massacres that the US perpetrated to conquer our people and take away the independence that had been won by Filipinos at the cost of much life and blood.

I began to understand why, in the aftermath of World War II and the “grant” of independence on July 4, 1946, the US promptly launched the Fullbright Program, a so-called educational and cultural exchange program. Patterned after the old pensionado system of the early years of the colonial regime, it aimed to maintain the Americanization of the Filipino intellectual in the context of the reformatted milieu of colonial apprenticeship for “nation-building.”

Over the years, every notable artist, writer, musician, critic, or academician was awarded a grant or scholarship in the US to experience firsthand and to attest to the bounty of living in America and the ideal of the American way of life.

In culture and the arts, “stateside” became the bar of excellence. In popular music, for instance, the Philippines had to have its own Elvis Presleys and Paul Ankas and Frank Sinatras, all widely adored American singers of the time. Filipinos exerted their best to sound like the real McCoy. Short story writers strove to become “the Andersons or Saroyans or the Hemingways of Philippine letters” by imitating the style and craft of these popular American fictionists. It became so pervasive in the mindset of the Filipino psyche that a label had to be coined for it: colonial mentality.

Quite apart from its intention, however, the colonial apprenticeship of Filipino intellectuals strayed in another direction when artists and writers began to challenge traditional literary norms, explore new forms, and take up serious themes on cultural identity and nationhood. An offshoot of this phenomena was the blossoming of creative writing in the native languages, such as Tagalog, Iloko, Hiligaynon, and Sugbuanon. The more daring literary outputs, written in these languages, went further to defy the safety of academic and philosophical inquiries and harked back to the patriotic ideals of the 1896 Revolution.

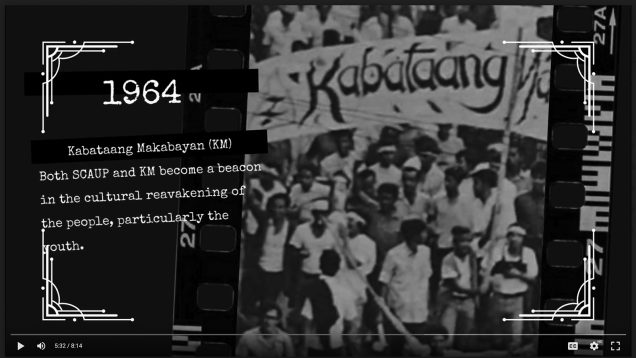

By 1961, a young professor by the name of Jose Ma. Sison organized the Student Cultural Association of the University of the Philippines; and in 1964, the militant Kabataang Makabayan (Patriotic Youth, or KM), right on the 101st birth anniversary of Andres Bonifacio. Joema Sison extolled the revolutionary virtues of the proletarian hero and underscored the urgent need to “finish the unfinished Revolution of 1896” by upholding the people’s anticolonial and anti-imperialist struggle to achieve genuine freedom and democracy.

By this time, artists, especially the writers in the native languages, had started to gravitate to the KM brand of activism by debunking New Criticism and the school of art for art’s sake. They created works of art that laid bare American neocolonial control over the Philippines and the elitist rule of the native aristocracy over the masses. Both the Scaup and KM became a beacon in the cultural reawakening of the people, particularly the youth. Progressive artists were drawn into the powerful stream of the nascent mass movement for national freedom and democracy.

By this time, artists, especially the writers in the native languages, had started to gravitate to the KM brand of activism by debunking New Criticism and the school of art for art’s sake. They created works of art that laid bare American neocolonial control over the Philippines and the elitist rule of the native aristocracy over the masses. Both the Scaup and KM became a beacon in the cultural reawakening of the people, particularly the youth. Progressive artists were drawn into the powerful stream of the nascent mass movement for national freedom and democracy.

In 1966, amid grinding poverty, First Lady Imelda Romualdez Marcos founded the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) to showcase “the true, the good, and the beautiful” in Philippine society. Essentially, it served to conceal the reality of the impoverished and dismal existence of the masses. But no matter, the CCP hosted foreign artists to prove that the Philippines had finally arrived on the world stage and was now in the league with “world-class” artistic icons.

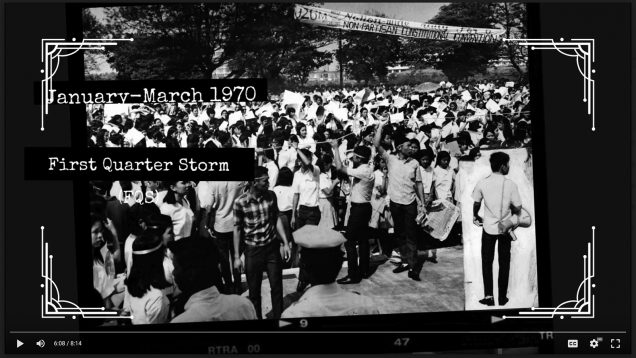

In 1970, the First Quarter Storm (FQS) broke out, spearheaded by the KM. It rocked the very foundation of the moribund Philippine society. Also described as the Second Propaganda Movement summoning artists and writers, it was a people’s crusade that materialized in a series of unprecedented protest actions, animated by a generation of youthful activists who were fired up with a new-found sense of nationalism and democracy. It exposed lingering social and political maladies and articulated the age-old despair and aspirations of the inarticulate, which became an avalanche of dissent and an agenda for revolutionary change.

The FQS played a major role in altering the consciousness of the people regarding the Philippine colonial past and the roots of the people’s basic problems; and how these had overwhelmed social structures, governance, the economy, justice system, foreign relations, peace and order, culture and the arts.

Activist-artists challenged one another to get down their ivory tower and be one with the people in their life-and-death struggle against oppression and exploitation and for national independence and democracy. They organized themselves into associations engaged in theater, visual arts, literature, and cultural research. These were all mass-based cultural organizations espousing people’s art as contraposed to the government-sponsored elitist art. A feverish organizing and mobilization of people’s artists and cultural workers and a blossoming of public art swept across the islands.

But it would be short-lived.

With full knowledge and concurrence of Washington, Ferdinand Marcos Sr. imposed martial law in the Philippines in 1972. Countless people’s artists and writers joined the underground resistance movement against the dictatorship. They helped form a clandestine but formidable antidictatorship network of media and cultural workers to counter the fascist propaganda of the US-backed Marcos regime.

In the grip of white terror unleashed by the Marcos dictatorship, writers learned to outwit the censors of martial law by creating what would be called “literature of resistance” and “literature of circumvention.” Theater artists employed traditional forms such as the religious drama “senakulo” to articulate the issues of the day and raise veiled commentaries about the martial law situation. They produced historical plays laden with subtexts about the present. In later years, they performed plays on national freedom and sovereignty and nuclear disarmament. Martial law notwitstanding, political theater became a major genre in what was to become as one of the liveliest periods in the Philippine literary and theater history. By the 1980s, much of the greed and corruption of the Marcos regime had been revealed, and the white terror of martial law dissipated – but the people, including the artists, had to endure torture and prison and make the supreme sacrifice.

In the grip of white terror unleashed by the Marcos dictatorship, writers learned to outwit the censors of martial law by creating what would be called “literature of resistance” and “literature of circumvention.” Theater artists employed traditional forms such as the religious drama “senakulo” to articulate the issues of the day and raise veiled commentaries about the martial law situation. They produced historical plays laden with subtexts about the present. In later years, they performed plays on national freedom and sovereignty and nuclear disarmament. Martial law notwitstanding, political theater became a major genre in what was to become as one of the liveliest periods in the Philippine literary and theater history. By the 1980s, much of the greed and corruption of the Marcos regime had been revealed, and the white terror of martial law dissipated – but the people, including the artists, had to endure torture and prison and make the supreme sacrifice.

Then it was 1986. For four days in February, Filipinos gathered in their millions to finally oust the dictator and put an end to the 21-year despotic rule, 14 of which under martial law. From the presidential palace, the US Air Force airlifted the Marcoses and their cronies to Clark Air Base on their way to Hawaii to flee the people’s wrath.

It was called the Edsa Revolution, but it was not. It was a people’s uprising alright and it must be credited for ousting a dictator. It was not a revolution because it did not change the power relations of elite rule over the masses, did not change the political and socio-economic structures that had kept the people in bondage through time. What changed were the faces in the exclusive elite club of governance. The Edsa Uprising facilitated the revival of the so-called liberal democracy that was bestowed by the US to its neocolony way back in 1946. So, in a manner of speaking, we were back to where we started.

A scene from “Suyuan, Himagsikan,” a short film by Bonifacio P. Ilagan.

Nevertheless, upon the installation of the Cory Aquino government, activist-artists and writers went full blast in organizing their ranks and propagating peoples’ art. Even as the democratic space that had been created by Edsa 1986 eventually constricted amid the political turmoil and natural calamities, artists continued to create and propagate the people’s struggles in their works.

In 2016, Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. launched the family’s campaign for a final grab at executive power by running for the vice-presidency. It sparked a renewed discourse on martial law and its implications, and artists took it up in their works. The triumph of Leni Robredo thwarted the Marcos plan. Rodrigo Duterte won as president and declared his so-called war on drugs the centerpiece of his administration. The bloody campaign became a theme in the artists’s creations and performances and thus made themselves targets of the Red-tagging vilification of the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict. The artists also joined in the campaign to assert Philippines sovereignty in the territorial dispute with China over the West Philippine Sea.

Then it was 2022. Ferdinand Marcos, Jr., by the trickery of a well-oiled machinery of historical distortion, fake news, and an army of trolls, garnered more than 31 million votes – if we are to believe Smartmatic and the Commission on Elections – to become the 17th president of the Philippines. Promptly, his camp proceeded to dig up the landmark projects of the late dictator’s regime, reviving the culture of fascist populism and neoliberalism and once again compromising whatever sovereignty and independence the Philippines possessed. There, too, was a spree of filmic productions aimed to pursue the rehabilitation of the Marcoses, but now bearing the imprimatur of officialdom.

No matter the enormity of the challenge, people’s artists take it up, and will persist in the continuing struggle to make Philippine independence a reality and engender a difference in the lives of the people.

People’s Chorale singing “Alin Pag-ibig Pa,” adapted from Andres Bonifacio’s poem “Pag-ibig sa Tinubuang Lupa.”

Comments (0)