Caregivers to get PR status upon arrival – albeit on a pilot program again

Caregivers to get PR status upon arrival – albeit on a pilot program again

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada Minister Marc Miller

June 25, 2024

By Veronica C. Silva

LJI Reporter

The Philippine Reporter

Good news, bad news? Caregivers can now come to Canada with a permanent residency status and not as temporary workers, Canada Immigration announced early this June. That’s the good news.

However, there are more questions about how the new pilot programs will roll out after the existing pilot programs have come to close this month.

Immigration Minister Marc Miller said the new pilot programs — with details to be announced later — will allow home care workers to come to Canada with permanent residency (PR) upon arrival. This is as two pilot programs – the Home Child Care Provider Pilot and the Home Support Worker Pilot launched in 2019 – have now been closed.

Miller added that with the new pilots, care workers will now be allowed to work in organizations providing care work, unlike previously when most care workers are working in home settings.

“This new pathway means that caregivers can more easily find proper work with reliable employers and have clear, straightforward access to permanent resident status as soon as they arrive in Canada,” said Miller.

Aside from the PR status, the previously contentious requirements to enable care workers to get PR status are also going to change. These include:

– dropping the minimum Canadian Language Benchmarks (CLB) to level 4 and

– requiring the equivalent of a Canadian high school diploma.

Two other requirements will qualify care workers to get PR upon arrival: having recent and relevant work experience and having an offer for a full-time home care job.

Martha Ocampo of Caregiver Connections, Education and Support Organization

Long campaign

PR status upon arrival has long been the appeal of caregivers and their advocates in Canada.

Advocates like Martha Ocampo are basking in their victory, which is 45 years overdue. Ocampo, of the Caregiver Connections, Education and Support Organization (CCESO), said she has been active in the campaign since the foreign domestic movement in the 1970s.

“This landed status upon arrival is a big deal for us [in CCESO], I would like to celebrate this victory,” said Ocampo, in a telephone interview with The Philippine Reporter.

“When we had discussions with Minister Miller [on June 3], he seems to understand, and we are happy, that they finally recognize that there is a need to provide PR for care workers,” she added.

Ocampo said landed status is important because “care work is essential work and permanent work. Canadian families need care workers to care for their children, their elderly, their sick … because there are not enough childcare services, services for the elderly and the sick.”

But while the announcement is a cause for celebration for CCESO and their fellow advocates, there is much work to be done as the recent announcement bring with it some questions.

One of the nagging questions is what happens to the care workers who have been in Canada for years now but are still waiting for PR status? Some of these workers have been undocumented already due to factors beyond their control. For example, some have been victims of work abuse, so they were forced to leave their workplace even at the risk of cancelling out the work permits tied to their employers. Some have been victims of unscrupulous work recruiters.

“There are still many left behind,” said Ocampo.

While it is difficult to pin down exactly how many PR applications are pending for the care workers who have completed their temporary work permit requirements, family separation takes its toll on temporary workers. For some care workers from the Philippines, family separation is longer than the years spent in Canada because some of them have come from other countries, such as Hong Kong and the Middle East, before coming to Canada as care workers.

And even after reunification after long years of separation, the families are strangers to each other, said Ocampo.

Regularization

Regularization

“It’s not good that they made it a pilot [program]. After two years, are they going to reverse it? That would be a very bad move – whatever government it is,” she added.

A pilot is not really what the migrant advocates are hoping for. Aside from waiting for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s marching orders to study regularization, there is the looming federal election, which could bring with it possible changes in policies.

The federal election is expected in fall 2025 but some want it earlier, according to polls. In Canada, immigration is a federal policy.

The announcement falls short of what advocates have been calling for – regularization.

In 2021, Trudeau tasked then Immigration Minster Sean Fraser to study the path to regularization for the undocumented. In fall 2023, Miller said he would present a proposal to his colleagues in spring 2024 on how this regularization could maybe look like.

“Many thousands of caregivers have faced abuse and exploitation and have been in limbo or have become undocumented over the last five years – Canada must now move urgently to implement a regularization program for undocumented caregivers to ensure no one is left behind,” said Jhoey Cruz of Migrant Workers Alliance for Change, in a press statement.

In the meantime, Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada said it wants to stabilize immigration levels to 500,000 up to 2026, cap the inflow of international students, and bring down the number of temporary residents to only 5% from the current 6.2%. All these are to keep Canada’s infrastructure, such as national housing crisis, at pace with population growth.

Canada’s population growth is fueled by immigration, which includes paths to permanent residency from different streams — temporary workers, refugees and asylum seekers, and temporary residents, such as international students.

Miller announced that the new program will cap care workers to an intake of 15,000 for this year, and this will be included in the 2024 immigration levels.

Other questions about the new announcement are about the other eligibility criteria, namely the work experience. That is, how current is the work experience that is going to be required? In previous programs, the requirement is six months. Another defunct program required caregivers to have 24 months of work experience before they were able to apply for PR.

Top source country

The Philippines is the top source country for care workers in Canada.

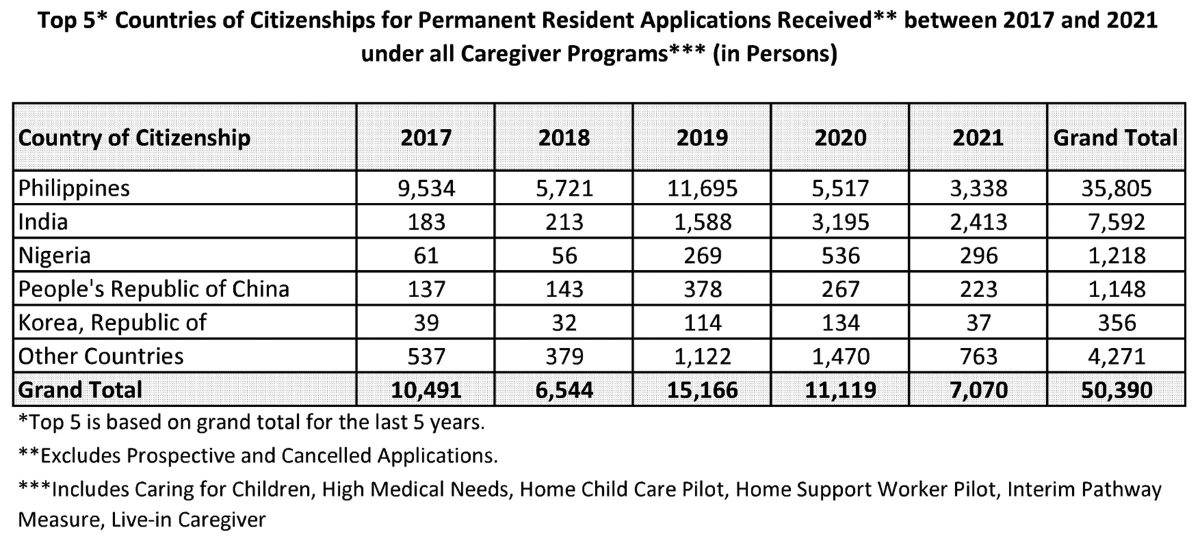

According to data from IRCC, the Philippines is the country of citizenship for applications for PR for care workers from 2017 – 2021 (according to data from an Access to Information request 1A-2023-17841 completed). In these five years, there were almost 36,000 applications received from Philippine citizens, compared to almost 8,000 for citizens from India, the country of citizenship for the next the greatest number of applicants. These are for all caregiver programs, including Caring for Children, High Medical Needs, Home Child Care Pilot, Home Support Worker Pilot, Interim Pathway Measure, and Live-in Caregiver.

The Philippines is also the top country of citizenship for work permit applications received for the same five-year period. For NOCs 4411 (Home Child Care Providers) and 4412 (Home Support Workers), there had been almost 29,000 applications received, including applications for extensions, for Philippine passport holders. In contrast, there had been only a little more than 7,000 applications received from nationals from India.

The care workers programs of Canada have undergone so many changes, including name changes, as they have remained pilot programs.

Ocampo and other advocates have long justified that the care needs of Canada remain a permanent need, requiring permanent programs, not pilot programs.

Comments (0)