A Filipino Diplomat’s EDSA ‘86: Breakaway in L.A.

A Filipino Diplomat’s EDSA ‘86: Breakaway in L.A.

Personal Account: Pedro O. Chan, Ambassador

17 February 2011, Ankara, Turkey

Those were heady and giddy days in February 1986-days of uncertainty, uneasiness and finally, of glory.

What the world recently witnessed real-time on live telecasts from Egypt must have been what we Filipinos had appeared to the whole world as it gaped with awe at the brave Filipino nation battling seemingly insurmountable odds 25 years ago on EDSA.

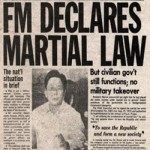

On a very early and still dark morning on the 22nd of February 1986, a prominent political exile from Marcos’s martial law regime phoned me at my home in Los Angeles and told me that the revolt against Marcos’s two decades of dictatorial rule had started in Manila.

“Are you joining us?” the exile asked me. Without a moment’s hesitation, I told Serge Osmeña III, “I’d been waiting for this for years, let’s go!”

At that moment, thoughts came flashing back to my mind, when I was still a UP student living at the poor man’s dormitory in Diliman, the Narra Residence Hall.

Those were troubled times, when the Metrocom would suddenly invade the campus, at one point raiding the nearby Kamia Residence Hall and pouncing on female co-eds suspected of being activists, inflicting indignities and physical violence on them, stealing items from the girls’ rooms, and there were even rumors of sexual harassment through bodily searches.

Also rushing back were those memories of my student days in Diliman when I was drawn into the UP teach-ins to politicize students about an impending Martial Law declaration by Marcos, the “First Quarter Storm” activism, the crude Molotov cocktail bombs that we would clumsily carry around in gasoline-filled soft-drink bottles in their wooden cases, the barikada and the “Diliman Commune” when then Senator Ninoy Aquino was the only sitting government official allowed by the rebelling students to enter the UP campus, Ninoy bringing with him family-size softdrinks, bread and biscuits, to the wild cheering of the protesting students. [Earlier than Ninoy, a known Marcos executive in Malacanang was reported to have tried to cross the barikada perimeter but was very rudely shooed away and widely booed with loud choruses from the student ranks of “P….. i.. mo! Bugaw ka ni Marcos! Alis dyan!”]

Then came to mind my days as a newly-passed Vice-Consul who was designated Special Assistant to the venerable General Carlos P. Romulo – Marcos’s long-time Foreign Affairs Secretary – particularly that fateful day on 21 August 1983 when we at the Department of Foreign Affairs were trying to chart the probable route of the returning hero and martyr-in-the-making Ninoy Aquino. That day, I got a call from the Chief of DFA’s Communications Office who broke the incredible news that Ninoy had been brazenly shot in broad daylight at the MIA [now NAIA] as soon as he disembarked from his China Air flight! Very telling was the reaction of my immediate supervisor then, the Department Chief Coordinator in the General Romulo’s Office when I phoned him to break the alarming news. “Why did they do it?”-he rhetorically asked, obviously referring to the military.

While I was still on the phone with Serge, it suddenly dawned on me that I was no longer the Acting Consul General of the L.A. Consulate. I was a mere third-ranking, young Consul barely two years into my first foreign posting in Los Angeles who had been designated as Acting Head of the L.A. Consulate in the absence of the regular Consul General (ConGen) and his Deputy ConGen, both of whom had been summoned or had volunteered to return to Manila to help in Marcos’s hastily-declared snap election campaign (courtesy of “Nightline” anchor Ted Koppel). I remembered that a couple of days earlier, I had met at the LA airport the Deputy ConGen who had just returned from Manila and immediately taken over as Acting Head of the Consulate. He even greeted me upon his arrival at the LA airport: “Ayos na ang buto-buto, Pete! Panalo na si Apo! Pati sa inyo sa Samar, inayos na ni General ang eleksyon!” He named the military commander in Samar then.

With that development, I told Serge that I would have to call and consult first with the recently-arrived Acting ConGen because with his return I had just relinquished official control of the Consulate and of our personnel. While dialing the Deputy ConGen’s residence phone, I was trying to think of how I could convince him to join our move considering that he had just returned from the Philippines on a Marcos snap-election campaign trip. When he came on the phone, I told him about the unfolding people’s revolt in Manila (I was not yet aware then that it was on EDSA).

I then asked if he wanted to join our plan to break away from Marcos. There followed a long, meaningful silence on the other end of the line. I nudged the other party by repeating my question, “Sir, are you going to join us?” Then his voice suddenly came alive when he told me in reply, “Kung sabagay napi-pinsan ko si General Ramos! Punta ka dito sa bahay, Pete, at gawa ka ng manifesto.” I then called my other colleague at the Consulate, Vice-Consul Willy Maximo, who did not need much coaxing and willingly told me he was tagging along to the house of the Acting ConGen in Cerritos where we would make public our breakaway stand.

Since Serge had informed me when he called early that morning that our then Honolulu Consul General (much later Philippine Ambassador to Washington D.C.) Raul Rabe had already broken away from the Marcos regime, we decided upon reaching Cerritos to immediately call ConGen Rabe in Hawaii. ConGen Rabe told me about his and his Honolulu staff’s stand-that they were no longer supporting Marcos’s government and would await the proclamation of the legitimate president. He further told me that they were staying put in the Honolulu Consulate office while they awaited word from Manila, adding: “You don’t have to follow us, Pete.” “No Sir, we will!” I immediately replied.

I would later learn from ConGen Rabe’s deputy that their morale was suddenly boosted (“Nabuhayan kami ng loob!”) when they learned that Los Angeles was also going to break away from Marcos. That Deputy’s revelation sounded to me like the story of the eleven apostles who, after they had kept to themselves like orphans inside the dinner room right after Christ’s death, suddenly felt the emboldening life breath of the Pentecost Spirit! The Deputy’s relieved reaction was quite understandable considering that the L.A. Consulate was then the largest Philippine foreign service post in terms of personnel complement in the USA, if not in the world, with a clientele of an estimated 800,000 or so Filipinos and Fil-Ams in the Southern California area.

Soon after, I saw a number of Los Angeles TV crews lugging their huge cameras as they trooped to the Acting ConGen’s Cerritos residence at about the same time that Serge and some of his friends among the “steak commandos”- as Marcos and his loyalists would derisively refer to the Filipino exiles in America who were fighting his martial law regime- would arrive. With the live TV and radio interviews going on at the Cerritos residence of the Acting ConGen and seen live on L.A.’s TV networks, many more Consulate staffers whom we had failed in our haste to call and alert about our daring move and were therefore unaware of what was going on, suddenly surfaced at the residence pledging their unity with our small fledgling breakaway group. They told me that they had heard on radio and TV what we were up to and wanted to lend their support to us that early.

As L.A.’s TV networks continued with their live coverage of our breakaway, it seemed that the whole world suddenly became aware of our daring and rebellious move. There had never been such “diplomatic mutiny” in the Philippine foreign service! It was simply unheard of! In the world of diplomacy, rarely if ever has the world witnessed a rebellion of one country’s diplomats who are generally known to “await and follow orders from Headquarters” having been trained and “brainwashed” to do so. I received calls from friends and colleagues in both in the US and in other countries asking about our move.

I clarified to many colleagues and friends who called that, although we in L.A. were the most conspicuous and had the widest media coverage owing mainly to L.A.’s ever active 24/7 media networks, it was actually our Consulate General in Honolulu which had initiated the breakaway a few hours earlier that fateful morning and we were just a close second. However, our people in Honolulu had kept to themselves and did not have extensive media exposure-if at all-so that the rebellion at the L.A. Consulate was much more prominently covered and seen in the U.S. and thus in the world’s tri-media, thereby giving the impression that we in the L.A. Consulate were the initiators of the breakaway in the whole Philippine foreign service.

During the interview at the Cerritos residence of the Acting ConGen, I was alerted by one of the anti-Marcos activists present that the Acting ConGen seemed to be giving his own prognosis of the unfolding events in Manila which the activist thought was inappropriate or unacceptable to say at the time. When I listened in on the interview going on in the living room, I overheard the Acting ConGen indeed giving his bold prediction that a military junta would take over from Marcos and it would rule the Philippines under the leadership of the prominent coup plotters. I then discreetly cautioned him to be circumspect about his fearless prognosis because we were not yet sure what was going to happen. He did not make mention of any military junta again after that.

Later in the day when we had returned to our rented apartments, I got a call from the Acting ConGen telling me that he had gotten physically exhausted from the successive media interviews and asked me to take over the interviews from then on. I willingly agreed, always having in mind the military junta prediction that he had made. As I was getting quite a large number of successive interviews on live TV, radio and the press, my refrain to the media people and TV journalists was to tell them that we who had rebelled in L.A. and those who converged on EDSA were fervently praying that Marcos would listen to the people and decide to step down very soon to allow the new President to take office peacefully.

I expressed pity and apprehension for those back home-our families, our friends, our compatriots-who were bravely fighting an entrenched dictatorship armed with nothing but their frail bodies, their ardent prayers and worn-out rosary beads and their floral offerings to their brother-soldiers, as they heroically tried to defy the military might of the Marcos regime in the face of the massive military tanks and fully-armed soldiers.

I emphasized the unimaginable consequences of the confrontation including heavy casualties and loss of innumerable precious innocent lives. In contrast, the worst that could happen to us who were safely overseas and far from the immediate physical dangers faced by those who were on EDSA, would – be long, extended and lonely exiles from our homeland if Marcos and his cohorts in government would not heed the popular clamor but stick it out in their positions of power.

A little later in the day, I called many of my friends in the teeming Filipino Community in L.A. to ask for their help in manning and helping us secure the Consulate office premises. I asked them to rush to the Consulate and to bring their firearms with them, as I also would. Our objective then was to prevent the known Marcos loyalists to get inside the Consulate offices as there was a very real danger that the loyalists would want to take over and occupy the Consulate.

When I arrived at the Consulate that same morning, a number of the aktibistas were already exhibiting their presence on the ground-floor of the Consulate building (the Consulate was near the top floor of a multi-storied office building on Wilshire Boulevard in Central L.A.) while some had stationed themselves at the Consulate entrance with guns discreetly tucked in their waistband. There were also two big, tall and brawny L.A. Police Department officers in plain suits whom I allowed inside the Consulate after they had identified themselves to me. They must have been sent by the State Department Office of California to ensure our physical safety and that of the Consulate premises.

Fortunately, although there were certain attempts by pro-Marcos elements in L.A. to enter the Consulate offices, we did not find any necessity to use our guns. I observed that many known Marcos loyalists were nonchalant-the type who would not dare fight tooth and nail the way the anti-Marcos “rebels” were more likely to do. It was to me a clear sign that they had sided with the then Consul General because of the perks that they had enjoyed for having affiliated themselves with the pro-administration umbrella group CONPUSO (Confederation of Philippine-US Organizations)-including frequent and regular trips to Manila, ready audience with the President and his First lady, and many other pa-sosyal benefits that came with being identified with the regime.

While almost every personnel in the L.A. Consulate had thrown their support for, or at least had expressed their inclination to join, the breakaway move, one Vice-Consul in the Consulate who hailed from the North was the lone conspicuous dissenter. When I asked him if he was ready to join us, he confidently told me in his usual booming voice, “Hindi bababa si Apo sa kanyang luklukan!”

That was loyalty if I ever saw one, obviously both personal and regionalistic, he and the dictator being both Ilocano. When media soon learned about the Consulate’s only recalcitrant Consul, reporters tried to smoke him out of his office room to persuade him to air his pro-Marcos views. He vehemently – turned down all requests for an interview. He continued to shut himself up in his room. The last I heard of him after he resigned soon after EDSA ‘86, he had taken on a job as a life insurance agent in L.A.

Later that same day, I received a telex message from the Law Offices of prominent American immigration lawyer in Los Angeles, Robert Lee Reeves, who catered to a large number of Filipino immigration and political asylum cases in L.A. While praising me and the staff for our bravery in having bravely defied Marcos’s mighty rule, he offered to handle gratis all the immigration cases of the Consulate staff and their families should Marcos decide to stay on in his seat of power thereby defeating our “rebellion”. [When later he came to congratulate us after he had learned that Marcos had left for Hawaii, he expressed obvious relief upon seeing the size of the consulate staff. He told me partly in jest, “Oh boy, am I glad you won, Pete! My office would have been flooded with immigration and asylum cases from the Philippine Consulate staff alone!”]

As the EDSA rebellion in Manila progressed, we kept vigil in front of the Consulate building. It was heartening and most encouraging to see many who had been fighting the Marcos regime for years and who had gone on exile in the U.S., join our vigil. There was, for example, someone who related to me how he had escaped to the U.S., after his young son was gunned down during a volleyball game altercation with certain personalities he said were identified with the ruling powers, and how he himself was mauled and had feared for his life even as he lay recuperating in a Manila hospital. He walked with a permanent and pronounced limp after the incident. [After EDSA ‘86, he would become an assistant to very a prominent opposition Senator who himself had gone on exile for many years in the U.S. after he almost succumbed to numerous shrapnel wounds he sustained during the Plaza Miranda bombing in the early 1970s.]

That same day, I got a telephone call from Manila. It was from a diplomat-assistant of our Ambassador to Washington D.C. who was concurrently Leyte Governor then. The diplomat-assistant told me that the Governor was most displeased with what I had done. “Masama ang loob sa ‘yo ni ‘Gov’ at ikaw pa daw ang namuno dyan,” he told me, obviously referring to my being a Waray like the “Gov”. He then informed me that I had been dropped from the lineal roster of officers by the DFA in Manila, as was Consul-General Rabe in Honolulu. He added that there was a real coup d’ etat being plotted by Defense Secretary Enrile and General Ramos and that it was uncovered by the President’s men. He then offered to help me get reinstated in the DFA provided I would retract the statements I made earlier that day withdrawing the L.A. Consulate’s support from the Marcos regime.

I did not have the heart to tell him that I had waited so long for that day of uprising against a despot, and that I would be an utter fool to take back the

7 – statements that I had already publicly made. So I just told him that I was not alone in our move in L.A. and I would just call him back. Of course I did not have any intention of calling him back nor of asking any of my colleagues to recant a single word of our statements. (Later, I learned that this diplomat was one of a number of DFA ambassadors and other personalities in Manila who signed a collegial DFA manifesto expressing support for Cory Aquino who had by then started to emerge as the sure winner in the people power struggle. He was later appointed DFA Undersecretary under ex-President Arroyo and was given an extension co-terminus with her presidential term; he is now over 71 years of age but continues to serve as DFA Undersecretary under Secretary Romulo and – ironically – President Noynoy Aquino.)

We waited and held vigil on the grounds in front of the Consulate building. For three long sleepless days we kept following the events on EDSA and anxiously awaited any breaking news that would come from Manila on what had emerged and came to be known the whole world over as “people power”. The 3-day vigil had its false alarms-albeit comical-the most notable being that famous jump by General Ramos on the “koryente” (fed false information) that President Marcos had left Malacanang. We would wait for another night of tense and suspenseful vigil before that much-awaited welcome news of Marcos’ flight finally came.

In the meantime, I received calls from my diplomatic colleagues in San Francisco, New York and Chicago. The call from a colleague in San Francisco was to ask what we were doing and what we intended to achieve with our very public move. After having explained to him what we had done and planned to do, I asked him to join us while the revolution was just starting so that he and his colleagues in our Consulate in San Francisco could avoid being branded as “opportunists” should they decide to make their move after it would become clear whose side would emerge as the winner in the people’s rebellion.

I soon found out after the dust had settled that that call to me was made after the officials in our San Francisco Consulate had received orders from DFA-Manila to proceed to Los Angeles and replace us, the rebellious L.A. Consuls. Unfortunately for our officials in our San Francisco Consulate, within a few hours after that call, the Filipinos in the community barged inside the Consulate offices, forced open its entrance door, tore down displayed photographs of the despised First Couple and other signs reminiscent of them, and took over the consulate. I could imagine that a similar incident would certainly have befallen the L.A. Consulate had I and my colleagues delayed our decision to break away from the Marcos regime given the teeming number of Filipinos in Los Angeles who were passionately against Marcos and his protracted rule. Several of those anti-Marcos Filipinos had remained political exiles for years in L.A. and had been

8 – waiting for the opportune occasion to voice out and demonstrate their anger against the Marcos government.

After that call from our San Francisco Consulate, a colleague in New York called the following day expressing his plan to join our breakaway, as did our Consul General in Chicago to whom I immediately dictated the manifesto that we had read earlier to the L.A. media. Those colleagues issued their own position papers and soon the rebellion got more widespread! Our Embassy in London also followed thereafter, as did some other foreign service posts which witnessed a torrent of anti-Marcos sentiments from among those in the Filipino communities within their respective jurisdictions.

The ensuing avalanche of support from many other embassies and consulates general, although a bit delayed having come as they did when the trend was already starting to tilt in favor of the EDSA revolutionaries, was as amazing as they were also very encouraging to us. In unity indeed, if not in numbers, there is strength. With the Philippine diplomats now rapidly voicing the exact opposite of the paeans that they used to mouth in praise of Marcos’ martial law regime, the Philippine foreign service-the first line of defense of the Marcos government, or of any government, for that matter-gradually but inexorably shifted away from Marcos’ institutionalized regime.

The euphoria that engulfed us and the whole Filipino community in Los Angeles on that third and fateful day on 25 February 1986 for sure could not match the sense of unexpected and incredible triumph of the people right on EDSA itself, but it was quite close. As a matter of fact, we drew our “high” and our reflected glory from the utter joy and ecstasy of those who jubilantly celebrated what has since been dubbed the “Spirit of EDSA ‘86”. It was with a deep sense of utter disbelief that we congratulated each other for the Filipino people’s triumph. We sighed with collective relief as we told ourselves, “We can go back home after all!”

Postscripts: When I presented in December 2009 my credentials to Georgia’s President Michael Shakashvili as non-resident Philippine Ambassador to Tbilisi, Georgia, I was shown and guided by the proud Tbilisi City Mayor to the famous balcony of the City Hall where Shakashvili had declared his now-famous “Rose Revolution” in November of 2003. I too felt a sense of pride and awe the way the Mayor did. Although I did not remind him that the Filipinos had started the “people power” phenomenon in modern times, I felt a deep sense of empathy standing on that balcony in faraway Georgia.

In Turkey’s capital city, Ankara, when my colleague the German Ambassador invited the Diplomatic Corps late last year to a photo-exhibit opening to commemorate the fall of the Berlin Wall, I congratulated him and told -him that we started it all in the Philippines with our EDSA ‘86. He acknowledged my comment although he seemed surprised and incredulous about what I had just told him. It is sad that the world seems to have forgotten the world-brand “People Power” that we Filipinos had started and which later got replicated in Romania, the USSR, the Berlin Wall, Georgia, and lately in Tunisia with its “Jasmine Revolution” and most recently in Egypt. The winds of change moved by that rebellious spirit of freedom are now threatening to sweep through Algeria, Yemen, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and even Libya, Iran and Bahrain seem no longer immune to this overwhelming passion for democracy.

Many say that not so much has changed since those heroic four days of EDSA ‘86, or that if there had been changes, these have been for the worse. Still others say that this is so because what we had done and undergone, though truly glorious for the Filipinos, was not a “real” revolution because it was far from being a bloody and change-generating revolution. The Romanian “people power” version that soon followed has been cited as an example of how real and fast change could be generated. That Romanian version of course resulted in the immediate execution of the ruling Ceausescu family dictatorship whose family members were lined up against a wall and executed by the dictator’s own heretofore loyal followers.

This may be so. Our revolution may not be the formulaic real bloody revolution that many countries have resorted to in the past to achieve much-needed change. But that is precisely why our “People Power” is a uniquely Filipino brand-for being peaceful and bloodless, for being Christian. As that APO Hiking Society’s tribute to EDSA ‘86 song goes: “Handog ng Pilipino sa mundo, mapayapang paraang pagbabago.”

What is much more important for us now is to realize that we, freedom-loving Pinoys, should not allow the gains of our initiative to be frittered away due to our own undoing. The very recent and unexpected welcome change in our society with its current governance could be viewed as another late-model and morphed “people power”. We should not waste this singular opportunity to pursue the revamp of our society that we ourselves had started 25 long years ago as a united people. EDSA ‘86 was a very rare display of Filipino togetherness for a common cause: our people’s freedom.

I wish we could continue to justify what we had proudly bannered and emblazoned on our T-shirts for one shining moment in our modern history. When P-Noy’s and our beloved Mother of Philippine Democracy, President Cory Aquino, went on a triumphal return visit to Los Angeles in 1989, we chose to boldly print on the fronts of our yellow T-shirts a patriotic slogan which was also a historic battle cry: Proud to be Filipino!

The dictator Marcos died in Hawaii in 1989, and his remains were kept in an improvised hillside crypt. A year later, Filipino diplomat Pedro O. Chan was assigned as Acting Consul General in Honolulu. He headed the Philippine Consulate General from 1990 to 1992, and helped supervise the orderly return to Manila of former First Lady Imelda R. Marcos who subsequently ran in the May 1992 Presidential elections. Later in 1993, when President Fidel V. Ramos allowed the Marcos remains to be returned to the Philippines, Consul General Chan was already on Home Office assignment in Manila but was again sent to Hawaii to accompany the late dictator’s remains when they were flown out of Honolulu. He has been Philippine Ambassador to Turkey since January 2009 with concurrent jurisdiction over Georgia and Azerbaijan.

Comments (0)