New Year’s Eve in the Philippines: New hopes, old heartbreaks

New Year’s Eve in the Philippines: New hopes, old heartbreaks

By Ed Maranan

Exclusive to The Philippine Reporter

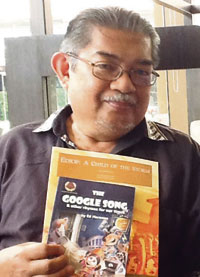

(Ed Maranan is a poet, fictionist, playwright, essayist, writer of children’s stories and poems, book editor, translator, and columnist for The Philippine Star. His published works include more than twenty children’s books, four books of poetry, and anthologized stories and essays. He has won some fifty literary prizes and awards. He was a political prisoner during the Marcos dictatorship. Starting this issue, he writes a regular column (see page 24 ) and occasional feature articles for The Philippine Reporter.)

Over the years, the main features of New Year’s celebration in the Philippines have included going to church, strolling in public places like parks and plazas with family and friends, setting off a variety of firecrackers or simply enjoying the sight of kaleidoscopic explosions of starbursts designed by craftsmen specially skilled in pyrotechnics, then settling down near midnight around the family table for the media noche, the traditional family dinner celebrating the dawning of the new year, with hope springing eternal that better times were just ahead. This is also a time for reunions, with close relatives and friends (particularly those without their own family gatherings) getting together to share a smorgasbord of classic native dishes as well as more contemporary foreign─flavored Filipino cuisine──everything thus from adobo and pancit to turkey and spaghetti, plus a wide variety of sweets and fruits, juices and spirits.

Another influence from the Chinese is the presence of round fruits at home to welcome the New Year and attract luck and prosperity.

The media noche is a rousing reprise of the more sedate Christmas Eve noche buena──the dinner close to midnight of December 24 that is meant to bring the family members in a ritual of thanksgiving for all the blessings received during the year just past, and it is right after the noche buena that the boxed, bagged, beribboned presents exchanged among the family members or especially bought for the young ones are opened. Because the feast of the media noche takes place just as the orgy of pyrotechnic explosions in the nightsky is nearing its climax, the Filipino universe turns into a frenzy of noise─making, through banging pots and pans, drums and cans and other tin and metal objects, tooting torotots more shrill than vuvuzelas, turning the CD player’s volume even louder, honking their car horns or setting of car alarms, lustily greeting each other a “Happy New Year” or shouting this greeting on the phone to relatives and friends living across town or abroad.

By the way, a new element has been added to the Filipino tradition of celebrating Christmas and New Year’s Eve, and this is ‘malling’──enjoying the sights, sounds, scents and savory offerings of the super malls: the new palaces of pleasure and emporia of the senses, the new spaces for human bonding, whose thousands of milling devotees dwarf the mini─multitudes still attending the churches and temples of worship in this country.

The most visible, audible and spectacular form of celebrating New Year’s Eve in the Philippines is of course fireworks, whose explosions are not confined to the hours before the “parting of the years” — paghihiwalay ng taon — but take place sporadically during the first weeks of Christmas, and well into the final hours of January 1. Fireworks have always played an important part in the lives of Filipinos. Apart from family togetherness and festive food, fireworks complete the essential elements of our New Year’s Eve celebration. One of the unrecognized fireworks geniuses in our country was a grand-uncle, Ka Filemon, who enjoyed until old age a reputation for being one of the finest makers of paputok in Batangas and nearby regions. His complex creations included whirling trompillos, Roman candles, multi-colored fountains and bedazzling skyrockets (kwitis). My father, before illness and old age enfeebled him, was ever the enthusiastic New Year’s Eve merrymaker who would spend a fortune on boxes of sparklers for the children, bundles and bandoleers of firecrackers — the Sinturon ni Hudas or “Judas’ belt” was a favorite of his — plus a full arsenal of assorted skyrockets.

The firecrackers we grew up with were next to harmless, at least the most common and most familiar of them — the rebentador, thin, inch-long paper-wrapped poppers bundled together in parallel rows. They literally made popping sounds in sequence, and may have been introduced in earlier times by the Chinese who came to the Philippines, these firecrackers being the traditional noisemakers used to drive off “evil spirits” in the Chinese’ own celebration of their New Year and other festive occasions. The venerable rebentador became childstuff compared to the next generation of firecrackers, starting with the trianggulo, followed by the bawang, the whistle bomb, and even one called the atomic bomb. That wasn’t the end of it. The latest listing of Philippine─made fireworks yields names such as Goodbye Philippines, Goodbye Gloria, Goodbye Bin Ladin, Giant Whistle Bomb, Super Plapla, Super Lolo, Gangnam Bomb, Crying Bading, End of the World, the Ampatuan, and a host of other exotic monickers for these purveyors of mayhem. The latest fireworks are designed to scare not only evil spirits but also sleeping babies, senior citizens who need peace and quiet, pitiful pets scurrying for cover, and people caught on the streets ever fearful of bodily harm. But much of the harm from fireworks is being done to those who set them off, to go by the yearly statistics of casualties brought to emergency wards and burn units of hospitals.

Like the global climate — or partly because of this — changes have been taking place in the Philippines, with a deep impact on how Filipinos celebrate seasonal events like Christmas and New Year’s Eve. Media does not fail to remind their viewers, readers and listeners that in the midst of all the revelry and festiveness of the season, Filipinos should not forget what has been happening to their more unfortunate countrymen in other parts of the land. And this year, it is the people of eastern Mindanao who have been hard-hit by typhoon ‘Pablo’ days before Christmas, who have suffered the brunt of devastation caused by nature — their untold suffering made worse by loggers and miners and their corrupt political patrons and protectors.

On New Year’s eve the worst disaster is entirely man-made and self-inflicted: the many deaths and injuries caused by fireworks, some of which are almost as powerful as the most lethal IEDs (improvised explosive devices) more common in the world’s conflict areas. As sure as day follows night, New Year’s Eve yields the most graphic photos and video footages on January 1: shattered or severed fingers and limbs, horrendous burns, seared faces and torsos, all because of the Filipino’s fascination for that most fatal mode of celebration: fireworks.

But then the TV host is quick to remind us that despite the tragedies and misfortunes of the year about to end, we should keep our hopes up, because 2013 — the Year of the Water Snake — is about to come upon us, and things could become much better. That, of course, was also said about the year 2012, exactly a year ago.

Comments (2)

Categories