The times they are a-changin’: A tale of folk and protest songs

The times they are a-changin’: A tale of folk and protest songs

The Country in the Heart

By Ed Maranan

IN THE WINTER OF 1962, between Christmas day and the New Year, sixty teenagers from as many countries arrived in New York City to attend a world youth forum sponsored by a top American newspaper. I was the youngest of the lot, all of sixteen and a promdi from the boondocks of a third world country, enjoying his first trip outside the homeland, now cozily huddled together with his fellow delegates in the heated confines of Sarah Lawrence College where we were expected to share stories of “growing up in a developing country”, and forge strong bonds of international solidarity while waiting for our American host families to pick us up and introduce us for several months to the American way of life.

Apart from the first magical encounter and enchantment with winter snow, what impressed me immediately was American music, the folk song in particular. Part of our introduction to America was the folk song as sung by an American student who was helping out in the weeklong orientation program at Sarah Lawrence. With youthful fervor, in a few days we had learned the lyrics and music of If I had a hammer, 500 miles, Donna Donna, and other standards of the genre. Around that time the Vietnam War was about to escalate, and it wasn’t long before the American folk song as we knew it would take on an angrier, edgier message and segue into the modern protest song, with Bob Dylan inspiring thousands of anti-war and anti-imperialist activists around the world with his plaintive songs of resistance and exhortation to action.

The provenance and relevance of the folk and protest song tradition, and the contemporary Filipino expression of political protest through this music genre, comprised the theme of Mga Awit Protesta, part of the UP College of Music regular monthly series of concerts, held a few months ago at the Abelardo Hall in UP Diliman. Prof. Edru Abraham, founder of the acclaimed Kontra-Gapi ethnic/world music ensemble, emceed and annotated the program which brought the full-house animated audience back to a period of rousing protest music which spanned several decades.

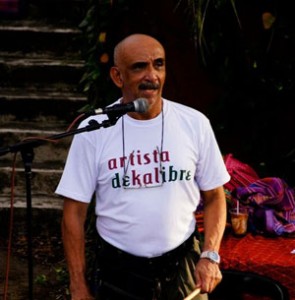

The featured performers were Lester Demetillo, one of the country’s leading exponents of classical guitar music but who is also known as a veteran folksinger and composer; Becky Demetillo-Abraham, a powerful presence in protest concerts since the martial law era, as one-half of the Inang Laya duo (the other half being Karina Constantino-David, sociologist-activist-composer and former Civil Service commissioner who made a guest appearance at the UP concert); Astarte Abraham, daughter of Becky and Edru who has established her own credentials as a theater, film, concert and performance artist; Mario Andres, a practicing lawyer who has always been a folksinger at heart, having played gigs in Manila’s folkhouses and the old Butterfly watering hole in UP before the martial law era; and Lory Paredes, a singer who used to be with the group Ambivalent Crowd, a former teacher and now an acupuncturist. Lester, Mario and Lory comprise an informal group with no band name, getting together only when invited to perform in a folk house gig or a major concert for a cause.

The first part of the concert focused on the folk-singing tradition as it emerged in the United States, deeply rooted in social movements such as the long struggle against slavery and racial discrimination, and the unrest during the poverty years of the 1930s Great Depression, inspiring the songs of Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, who in turn influenced the singers and songwriters of the 60s and 70s, notably Joan Baez, Peter Paul and Mary, Bruce Springsteen and others.

The songs sung during the first half of the Mga Awit Protesta concert would have been familiar to folkies of the late 50s and early 60s generation (including this senior citizen whose memories of the 1962 youth forum came flooding nostalgically back): Day is done by Peter Yarrow; When the ship comes in, Blowin’ in the wind and The times they are a-changin’ by Bob Dylan; One tin soldier by Dennis Lambert and Brian Potter, There but for fortune by Phil Ochs, If I had a hammer by Lee hays and Pete Seeger, and If I had my way by the Rev. Gary Davis.

The second part was a tribute to the Philippine nationalist tradition in music. The program notes described this tradition as encompassing the themes of resistance against colonialism and oppression, struggle for independence and social justice, and lays down the beginnings and trajectory of Philippine protest songs from the Katipunan and the Revolution of 1896 to the struggle against the Marcos dictatorship and all the regimes that succeeded it.

Featured were the compositions of Lester Demetillo, Inang Laya, Ramon Ayco, Jane Po and Luis Jorque. Demetillo, as early as 1989, had set to music poems in the social-realist vein written by the durable multi-genre writer in Filipino as well as painter/film-stage-TV-actor Domingo Landicho, Karina Constantino-David and this writer (all former activists and UP professors). The lyrics, with Lester’s music in turns poignant or militant, resonate with the struggle of Filipinos against martial law and dictatorship, and express the aspirations of the common people. Included in this section were Landicho’s Paano tutula, Mundo ng bata, Batang pulubi and Anakpawis, David’s Japayuki, Macliing Dulag, Walang lagay, and Kasama sa kalsada, Ayco’s Babae, Inang Laya’s Atsay ng Mundo, Jane Po’s Titser, Ed Maranan’s Sambutani and Langay-langayan, and Andres Bonifacio’s Pag-ibig sa Tinubuang Lupa.

nang Laya: Karina David-Constantino and Becky Demetillo-Abraham, with Lester Demetillo. PHOTOS: ROGER EVANGELISTA

Most of these songs were first performed in 1989 by the AlayAni—a troupe of poets and musicians formed by Edru Abraham—in a series of concerts billed as Tula at Awit sa Bayan at Bayani which toured all over the country under the auspices of the Cultural Center of the Philippines.

The revival concert was dedicated to the memory of Darnay Demetillo, long-time professor and founder of the Fine Arts Program at the University of the Philippines in Baguio, and Susan Fernandez—an AlayAni vocalist, and a highly regarded musical artist at countless mass actions, protest concerts and folk gigs for over two decades, from the Marcos era to 2009, the year she died from cancer.

Comments (0)