Filipino medical students call for more representation in medicine

Filipino medical students call for more representation in medicine

U of T medical students welcome Dr. Gigi Osler (3rd from right), President of the Canadian Medical Association.

By Gian Agtarap and Braydon Francis

Filipinos are no strangers to healthcare. As a people that pride themselves in good hospitality and compassionate service, it’s no wonder why many Filipinos gravitate towards the healthcare field, and do a fantastic job at that. However, while there appears to be a large number of Filipinos choosing to pursue a career in nursing and other allied health professions, the same cannot be said about medicine. Indeed, multiple studies show a long-standing lack of representation of Filipinos in Canadian medical schools1.

Why is this the case? When the underlying values of nursing and other allied health professions so closely coincide with medicine, why do so few Filipino-Canadians go on to become physicians? Is this because of a lack of mentorship and support for young Filipinos interested in medicine? Or is it because of the strong familial pressure to go into more certain (i.e. less competitive) fields? It’s no secret that medicine is a demanding career, both in time and money, which can act as a deterrent to aspiring students. Whatever the reason, the disparity of Filipino physicians is a curious topic that has sparked the interest of medical students at the University of Toronto (U of T).

Braydon Francis, a second year medical student at U of T, gained admission into the MD program after having completed a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BScN) at Ryerson University.

“Coming from a nursing background, I noticed that there were many Filipino students in my class. However, very few of them had any intention of pursuing a career in medicine. I recall speaking to one of my Filipino classmates about why she never considered becoming a physician. Her response was since she comes from a family of nurses, it seemed only natural to follow in their footsteps. Like her, many of my relatives were nurses or health care workers; none of which were physicians. As the first person in my family to aspire to become a physician, there was a lot of uncertainty and confusion regarding the process of pursuing medicine – the constant stress, the uncertainty, the innumerable hours of studying. Because of that, my mother suggested that I first finish my BScN and then take a break from school to start working and earn money. I can empathize why it would be hard for them to see their child go to such lengths to achieve a goal that is so uncertain.”

The panelists and host from the FAMS most recent event, “Filipinos in Medicine.”

From right: Dr. Ivy Oandasan, Gian Agtarap, Dr. Eileen de Villa, Dr. Ryan Figueroa.

Gian Agtarap, another second year U of T medical student, expressed similar sentiments regarding the lack of mentorship in his academic journey to medicine. He says:

“I completed my undergraduate degree at McMaster, with a Bachelor in Health Sciences. The program was notoriously known for being a pre-med program, something I would not have known if not for my neighbour, who graduated through the same program. During my time there, many of my classmates came from physician families. As such, they knew which activities to do, like research and academic opportunities, in order to get into medical school. This was in complete contrast to my experience — I knew very few people who went through the Canadian medical school system. The lack of mentorship, social capital, and knowledge of the system put me at a disadvantage in comparison to my peers, and I can imagine this is also the case for many young aspiring Filipinos.”

Narratives like these, or at least aspects of it, seem to resonate with the Filipino youth. The lack of guidance and support, the parental pressure to go into other “more secure” fields, and the unwillingness to commit to 8+ years of education seem to be common themes across the Filipino community. There is nothing inherently wrong with Filipinos having a propensity towards certain fields, and in fact Filipinos should pride themselves on excelling in careers like nursing. However, the lack of representation in medicine specifically, does pose barriers for not only aspiring youth, but also patient populations.

Several studies have demonstrated improved patient care and satisfaction when patients receive care from providers from the same cultural background as them2,3,4. This may be due to a sense of familiarity and relatability between patient and physician. While these studies are mainly focused on Black and Latino populations in the USA, their findings may be generalized to other ethnic groups. Therefore, this evidence suggests patient care and satisfaction would be improved if Filipino-Canadians were cared for by Filipino health care providers. However, further research on the Filipino-Canadian patient population must be conducted in order to confirm this.

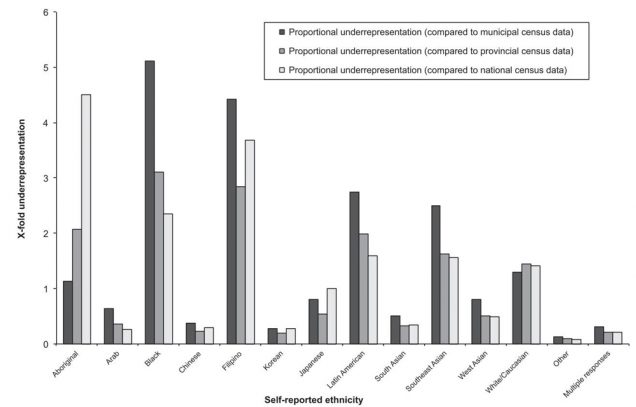

A graph from a study by Young et. al. (2012) highlighting the proportion of medical students in four Canadian medical schools compared to municipal, provincial, and national census data.

In light of this absence of research and attention to the matter, current U of T medical students are at the forefront of increasing conversations around Filipino equity and representation in medicine. Led by President Gian Agtarap, they have started the Filipino Association of Medical Students (FAMS), which has officially been ratified by the U of T Medical Society. The group’s mission is to address the issues of underrepresentation and inequity in medicine as it applies to the Filipino community. For instance, back in 2018, they invited Canadian Medical Association President and ENT surgeon Dr. Gigi Osler, who is half Filipino, to speak about diversity and equity in medicine.

Last December, they again hosted their annual event “Filipinos in Medicine”, this time featuring Dr. Eileen de Villa, the Medical Officer of Health for the City of Toronto, as the keynote speaker, with Dr. Ivy Oandasan (Professor, Dept. of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto; Director of Education, College of Family Physicians of Canada) and Dr. Ryan Figueroa (President of the Filipino Canadian Medical Association) as panelists. Through community outreach events such as these, as well as media presence and research, the FAMS hope to foster a sense of camaraderie between Filipino medical students across Ontario while providing mentorship to aspiring Filipino pre-medical students.

Conversations surrounding equity, diversity, and representation have started at medical schools across the country. Initiatives like the Black and Indigenous Student Application Programs at U of T and the Diversity and Social Accountability Admissions Program at the University of Saskatchewan were created in order to address the underrepresentation of these groups in medical school admissions. Given that Filipinos comprise the fourth largest visible majority in Canada and are the current leading source of immigrants in Canada, we hope that the Filipino community will begin to join in on the conversation of representation in medicine.5

To that end, we encourage more Filipinos to aspire to pursue a career in medicine. The path forward may seem daunting and overwhelming, especially considering the lack of mentoring Filipino physicians. However, with the birth of the FAMS at U of T, we plan to act as a resource for any aspiring pre-medical students hoping to achieve their dreams. The current and future Filipino-Canadian community needs you.

————————————-

References

Young M, Razack S, Hanson M, Slade S, Varpio L, Dore K et al. Calling for a Broader Conceptualization of Diversity. Academic Medicine. 2012;87(11):1501-1510.

4. Garcia J, Paterniti D, Romano P, Kravitza R. Patient preferences for physician characteristics in university-based primary care clinics. Ethnicity & Disease. 2003;13(2):259-267.

Gray B, Stoddard J. Patient-Physician Pairing: Does Racial and Ethnic Congruity Influence Selection of a Regular Physician? Journal of Community Health. 1997;22(4):247-259.

Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, Vranizan K, Lurie N, Keane D et al. The Role of Black and Hispanic Physicians in Providing Health Care for Underserved Populations. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;334(20):1305-1310.

The Daily. Immigration and ethnocultural diversity: Key results from the 2016 Census. [Internet]. 2017 [cited 20 April 2019];. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025b-eng.pdf

Comments (1)