Amid COVID-19: Caregivers caught in a ‘Crisis Within A Crisis’

Amid COVID-19: Caregivers caught in a ‘Crisis Within A Crisis’

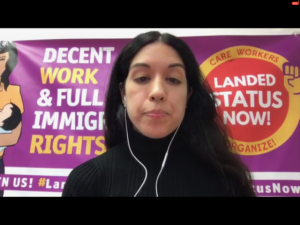

iana Da Silva, facilitator/moderator of the press event.

By Veronica Silva Cusi

The Philippine Reporter

TORONTO (Nov. 2) — New report documents caregivers’ allegations of abuses and exploitation as they were practically trapped in their workplaces and underpaid when a COVID lockdown was imposed in Canada

When COVID-19 forced almost the entire country in lockdown last spring, migrant caregivers found themselves trapped in their employers’ homes, working long hours with no extra pay. Worse, they found themselves anxious and stressed as they couldn’t spend time with friends, and some couldn’t even remit funds to their family back home who are also facing financial anxiety due to the pandemic.

Their struggles are documented in a report titled “Behind Closed Doors: Exposing Migrant Care Worker Exploitation During COVID-19,” released last October 28 by caregiver groups affiliated with the Migrant Rights Network (MRN). The report is based on a survey of 201 migrant care workers from across the country. It notes that nearly one in two respondents worked longer hours during the pandemic, and over 40 per cent of respondents said they were not paid for the extra work. Each worker’s underpaid wages are estimated to average $6,552 per month for the last six months.

Diana Da Silva, organizer for Caregivers’ Action Centre (CAC), said in a virtual press launch that the report documents how respondents, most of them racialized, shared their experiences of abuse, exploitation, fear and stress during COVID-19.

CAC is a self-organized group affiliated with MRN.

“Our report shows that 48 per cent of respondents reported working longer hours, ranging from 10 to 12 hours a day. One in three respondents who lost their jobs during COVID-19 are struggling to find a new employer to sponsor them in order to obtain a Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) and the 24 months (required for permanent residency),” said Da Silva.

The LMIA is a necessary document before a migrant worker can be hired (https://www.cic.gc.ca/english/helpcentre/answer.asp?qnum=163&top=17). A positive LMIA indicates that there is no locally available worker to fulfill the job.

Karen Savitra in a pre-

recorded video in a park

telling her story.

Karen Savitra, a migrant caregiver from the Philippines and a member of CAC, said in a pre-recorded video aired during the virtual launch, that she was working 12 hours a day for five days for only $1,440 per month. Due to the pandemic forcing children to learn from home, her work hours were stretched to include helping the children with their schoolwork and projects.

The report notes that with most people staying at home during the lockdown, this creates “tremendous labour intensification” on the part of caregivers because they are doing tasks that they were not doing previously, such as disinfecting and cleaning often.

Just last month, Savitra’s employer moved farther north of the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) to avoid the COVID hotspots. But she said she didn’t join the family because she will not be provided a room of her own, and she couldn’t find a place to visit during her day off as public transit was not readily accessible and she would be away from friends.

Marlyn Lopez of the Caregiver Connections, Education and Support Organization (CCESO), a Toronto, Ontario-based group of volunteers serving caregivers, newcomers and migrants, said that some employers do not allow caregivers to meet up with their friends, buy groceries or remit wages to families back home.

“Social isolation can lead to severe anxiety, depression and a deep longing to reunite with loved ones,” added Lopez.

Savitra said she is currently looking for another employer who can give her a new LMIA document that would allow her to continue to work and apply for permanent residency.

While she already finished in 2018 the 24 months required to apply for PR status, she said could not apply for permanent residency (PR) because her employer didn’t comply with all the requirements.

Savitra said completing 24 months is difficult as not all employers are good. Still, she said caregivers tolerate employers’ violations [of labour laws?] to complete the requirements and maintain their status.

Judy Cabato airs grievances in pre-recorded video.

Screen grab from CAC video.

This nagging uncertainty over status is shared by fellow Filipina migrant caregiver Judy Cabato a member of the Vancouver Committee for Domestic Workers and Caregivers Rights, which is also a co-author of the MRN report. In a taped video at the press launch, Cabato said she was laid off in April, and her health coverage and social insurance number expired when she was laid off. While she has completed the required 24 months to allow her to apply for permanent residency, she still has to get another employer as she goes through the application process. Currently, she is in what the report refers to as a state of limbo.

Caregivers who are awaiting results of their PR applications are in a state of limbo, or so-called in “implied” status. While allowed to stay in the country pending results of their application, “migrant care workers on implied status are unable to renew health coverage.”

“The longer Cabato is in limbo, the longer it will take her to be reunited with her family,” said Da Silva.

“Care workers who have become undocumented due to long delays in the renewal of their work permit continue to work long hours without getting fully paid,” said Lopez of CCESO.

The report notes that getting an LMIA takes from three to six months under normal circumstances, and much longer during this pandemic.

The report adds that loss of job means no housing for these care workers. The report estimates that there are about 25,000 migrant care workers in Canada, most of them living with employers even during the pandemic.

While Savitra was able to access COVID support, like the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), for only a month before the program ended, she is now one month without pay as she transitions to the new Employment Insurance which took over from the CERB.

The report findings indicate that one of three respondents were having difficulty accessing income supports such as CERB or EI.

“COVID-19 has created a cascade of crises, shattering hopes for many. We now fear that permanent residency is slipping further away from us,” the report reads. “Immigration rules are responsible for this cascade of crises.”

Those with expired work permits but can’t find another employer lose their status and become undocumented, making it difficult for them to access supports.

The report reads: “The newly announced Canada Recovery Benefit is only available to workers with a valid Social Insurance Number. This automatically excludes the growing number of care workers who are falling into implied status because of processing delays and issues finding work as a result of the pandemic.”

Status for All

Such uncertainties and workplace exploitation have again prompted migrant groups to call for full status for temporary foreign workers.

“COVID-19 has exacerbated an existing crisis for migrant care workers, and permanent status is the only way to allow workers to protect themselves from exploitation,” said da Silva. “Caregivers are facing a crisis within a crisis, and … the only solution is to grant them permanent residency status and have them reunited with their families.”

“COVID-19 highlights the need for care work is an essential and permanent work,” said Lopez. “Granting PR (status) to undocumented care workers and those under temporary work permit will ensure that Canada will never again have shortage of people with skills that are deemed essential care work. Care workers should be given a PR (status) with their family upon arrival.”

The report is also recommending that the 24-month requirement be reduced to 12 months and open work permits granted immediately. Currently, migrant care workers can only apply for open permit after completing 24 months of qualified service.

The survey conducted in the last two months involved 201 care workers from Ontario (141 respondents) , B.C. (40), Alberta (14), Quebec (3), Manitoba and New Brunswick (one respondent each).

The Migrant Workers Alliance for Change is also a report co-author. The reports states that the recommendations in this report are endorsed by Alberta Careworkers Association, PINAY Quebec, Migrante Canada, Migrante Alberta, and Association for the Rights of Household and Farm Workers (ADDPD/ARHW).

More recommendations can be found in the report: https://migrantrights.ca/behindcloseddoors/

Comments (0)