Yolanda after 6 years — Pain and devastation remain

Yolanda after 6 years — Pain and devastation remain

By Althea Manasan

By Althea Manasan

The Philippine Reporter

It’s been more than six years since Super Typhoon Yolanda swept through the Philippines, killing at least 6,300 people and leaving a trail of destruction in its wake — but thanks to corporate greed and lack of action to combat climate change, the hardest hit continue to suffer years later.

Filmmaker Sean Devlin

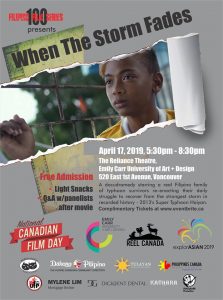

That was the key message at an event on Jan. 20, where almost two hundred people gathered at a cinema in downtown Toronto to watch When the Storm Fades, a 2018 film made by Filipino-Canadian filmmaker Sean Devlin.

It was part of a one-night, Canada-wide screening that took place in 15 cities across the country, including Vancouver, Edmonton, Ottawa and Halifax.

After the screening, members of local and international community organizations led the audience in a discussion about the devastating consequences of climate change.

When the Storm Fades, which premiered at the 2018 Vancouver International Film Festival, is set in Leyte three years after the typhoon, and tells the story of the Pablo family as they try to rebuild while also struggling with the grief of losing family members.

It also features two well-intentioned but clueless white Canadians, who travel to the region and volunteer their efforts to the recovery by planting mangrove trees along the shoreline.

Described by the director as a “docudramedy,” the film blends drama, comedy and documentary. It stars the real-life Pablo family — Abner, Nilda, Arnel and Lovely all playing themselves — and draws on their actual experiences.

“You don’t see many films of that type in regards to what’s happening in the Philippines,” said Fatima Barron, noting that most films exploring systemic issues in the country are documentaries.

“It was very explicitly a satire docudramedy, so [the filmmakers] were able to explore those themes better than a documentary that’s trying to be unbiased.”

Fatima Barron, Anakbayan Chairperson

Barron is the chairperson of Anakbayan Toronto, an organization of Filipino youth that was asked by the filmmakers, who were not in attendance, to lead the post-screening discussion. She was joined by Andy Tran, a representative from the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines (ICHRP).

They fielded questions from engaged audience members, many of whom were non-Filipinos, about how deforestation in the Philippines is distorting the climate, how multinational corporations have been moving into Tacloban in the wake of the storm and engaging in “disaster capitalism,” and what people overseas can do to help victims of climate change around the world.

“It was great that we had a conversation, that we [as community organizers] were there. That’s not something that happens at a lot of screenings,” said Ysabel Tuason, Anakbayan Toronto’s deputy secretary general.

“People were asking arts questions at first, but I think when people realized we were organizers, the dialogue was more ‘How can we help?’”

Ysabel Tuason, Anakbayan Toronto’s deputy secretary

Tuason herself can relate to that desire to help victims halfway around the world. Although she was raised in Canada, her mother is from the town of Carigara, just outside Tacloban.

She visited the area in 2014, just months after the storm, and remembers on the ride home from the airport seeing destroyed houses and signs saying “Help us” and “God save us.”

“I was just in shock,” Tuason said. “At the time, I just wanted to do anything, but I didn’t really know how to meet people.”

Through joining organizations like Anakbayan Toronto, she discovered the power of community organizing.

“I feel like I’m coming at things with a more justice-based approach as opposed to voluntourism,” she said.

“It’s hard to connect the three basic problems of Filipino society — and I understand them to be feudalism, bureaucratic capitalism and imperialism — to the typhoon…It might seem like all you can do is plant mangrove trees.”

Marissa Cabaljao, real-life peasant leader and

community organizer

The effectiveness of voluntourism versus community organizing is a theme that’s explored in When the Storm Fades. The experience of the white Canadian volunteers is juxtaposed with scenes featuring real-life peasant leader and community organizer Marissa Cabaljao.

In the film, Cabaljao, who serves as secretary general of The People Surge, the Philippine’s largest alliance of storm survivors, can be seen rallying community members and speaking out against corporations moving into the regions affected by the storm.

In addition to these screenings, the filmmakers are also working on a campaign to send Cabaljao on an international speaking tour to highlight how climate change is affecting people in the Philippines.

Barron said she appreciates that the filmmakers included a local perspective, one that shows Filipinos fighting for human rights.

“We’re not this sad bunch of people affected by climate change and not doing anything about it.”

Comments (0)