Social Planning Toronto Report: Racialized groups in housing crisis

Social Planning Toronto Report: Racialized groups in housing crisis

The Quinon family, headed by matriarch Nancy (far left), live in a two-bedroom rental in the west end. Not in photo is Nancy’s daughter-in-law, who joined the family from the Philippines last October.

(Photo provided by Nancy Quinon)

By Veronica Silva Cusi

The Philippine Reporter

A recently released report on housing in the City of Toronto indicates that people who identify themselves as belonging to a racial group are most likely to experience a housing crisis compared to non-racialized groups. Among these racialized individuals, those who identify themselves as our kababayans (compatriots) have the highest percentage living in unsuitable or overcrowded rentals.

“The proportion of racialized individuals living in unsuitable housing is almost three times that of non-racialized individuals,” read the report by Social Planning Toronto released on November 17. The report highlights “marginalization and social exclusion associated with racialized and immigrant status” in rental housing in Toronto.

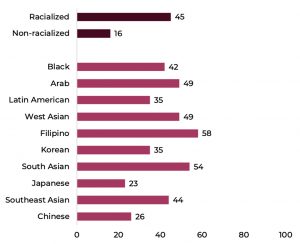

The percentage of Filipinos living in unsuitable housing is 58 per cent, the highest among racialized individuals, says the report. The next racialized individuals — also known as visible minorities — with a high percentage of the population living in unsuitable housing are South Asians (54 per cent), and Arabs and West Asians (both at 49 per cent).

By “suitable housing,” the Social Planning Toronto report uses the Statistics Canada definition based on National Occupancy Standard (NOS) that measures the ratio of number of bedrooms and number of people living in the dwelling place. Unsuitable housing basically means overcrowding.

Nancy Quinon, 58, and her three adult children, have been living in in a two-bedroom rental building in the west end since 2012. Last October, one of the adult children reunited with his spouse from the Philippines, bringing the total of adults to five.

“I cannot afford the rent on my own,” said the single mother who arrived in Toronto in 2006 as a live-in caregiver. “Madami pang utang na babayaran (There are still so many bills to pay)” from expenses from her remittances to her children in the Philippines and, later, for processing documents for permanent residency (PR) for herself and her children.

In the east end, former caregiver Pearlita, 65, and her two adult sons are living in a one-bedroom rental apartment. The widowed mother landed in Canada more than 12 years ago and is now also a Canadian citizen.

“Nasa pag-aayos mo na ng bahay yan (it all depends how you manage your space),” was how she explained her living arrangements. “Mukhang condo-style amin (Our place looks like a condominium).”

Both former caregivers used to live in boarding rooms with other fellow caregivers or family. Soon as they were reunited with the families they left behind in the Philippines, they moved out of their boarding homes to another overcrowded accommodation.

(Figure 33:)

Percentage of Population in the City of Toronto

Living in Rented Dwellings that are

Unsuitable (2016), by Racialized Status

Source: Spaces and Places of Exclusion: Mapping Rental Housing Disparities for Toronto’s Racialized and Immigrant

Communities by Social Planning Toronto

Core Housing Needs

The report of Social Planning Toronto is based on 2016 census data of immigrants who are renting. The report assessed the “core housing need” as an indicator of a housing crisis in the city, which is home to 2.7 million, 51 per cent of which identify as visible minorities.

Aside from housing suitability, the core housing need indicator also measures affordability, i.e., the proportion of household income that is spent on shelter; and adequacy, which measures whether tenants say their dwellings need major repairs.

Over 1.1 million Toronto residents, or 42 per cent of the population, live in rented dwellings. Forty-six per cent of racialized individuals live in tenant households compared to 36 per cent of non-racialized individuals.

The report also compared the housing needs of newcomers, defined as residents who immigrated and gained PR status less than 10 years at the time of the 2016 census, with long-term immigrants. According to the report, newcomers and long-term immigrants have higher rates of core housing need, at 39 per cent and 38 per cent, respectively, compared to non-immigrants, at 31 per cent.

“Data suggest that racialized individuals are sacrificing living in suitable housing as a strategy for dealing with housing that is increasingly unaffordable,” said Naomi Lightman, report co-author and assistant professor, University of Calgary, said in an interview.

She also noted that as housing prices have increased dramatically in the last few decades, especially downtown, Toronto has become increasingly not accessible to newcomers.

“Rental downtown is not serving families with larger households with their smaller size units and higher cost,” said Lightman.

The report also highlights housing inequalities in some city wards. Lightman cited York Centre (Ward 6), which includes “Little Manila” in the Bathurst and Wilson area, there is a huge divide in housing suitability between racialized and non-racialized individuals.

In Toronto Centre (Ward 13), which has the highest rate of newcomer population living in rentals at 81 per cent, there are more long-term individuals who have been living in rentals. The Philippines is the top birthplace of people living in Toronto Centre.

Cultural

Both Nancy and Pearlita said their families are saving up — para yung sunod na bahay namin e amin na (so that the next dwelling we move into will be our own home), said the two women almost in unison, even though they were interviewed separately by The Philippine Reporter (and as far as this reporter knows, they don’t know each other).

Such reasoning is not surprising to our culture, explained Pinky Paglingayen, a Filipino settlement worker with The Neighbourhood Organization (TNO), a settlement agency with housing programs funded by the City of Toronto.

Paglingayen said it is embedded in Philippine culture that families stay together until we can save up to purchase our own homes.

“Housing is an issue among our service users,” said Alaka Brahma, TNO’s manager of Family & Wellness, which is responsible for housing programs. “Many families are looking for affordable housing. Affordable housing does not exist in Toronto.”

Racialized individuals also face discrimination

Aside from financial challenges, Brahma said racialized individuals also face discrimination from landlords. Based on TNO’s research, they found out that some landlords deny tenants room availability depending on their English skills and whether they are on social assistance.

“They [landlords] are not supposed to discriminate on these grounds, but they do,” said Brahma, who has been working in housing services for almost 20 years.

But she added that some renters choose to rent because they are comfortable in their community.

COVID

Naomi Lightman, co-author, assistant professor, University of Calgary. Photo provided by Social Planning Toronto

While the study covered 2016 data, Lightman said “many of the trends that we see have likely been exacerbated over time, and the COVID-19 pandemic has made these trends that we see even more problematic and dangerous for many of the residents, especially around overcrowding,” said Lightman.

The report highlighted the relationship of the housing crisis to the COVID-19 pandemic by citing data on racialized individuals, low income, unemployment and households.

The concerns are with basis.

In their COVID-19 modelling presentation on November 26, the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table noted that some “long-standing structural factors,” such as household density and occupation, put some communities at higher risk of exposure to COVID-19.

Adalsteinn Brown, advisory table co-chair and dean of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, said in a press conference that “there are communities that are facing persistently much higher levels of COVID-19 infection.”

Their findings, also based on 2016 census and other data, show that for communities with the lowest level of suitable housing, the level of COVID infection is the highest. “And it has been the highest in both the first and the second wave,” Brown said. In contrast, communities with the highest levels of suitable housing have seen the lowest COVID-19 infections in both waves.

NEXT Steps

The report puts forward several policy recommendations, including a moratorium on eviction and funding for an independent office for the Housing Commissioner in the 2021 budget.

“We see this [office] as instrumental to implementing more progressive, equitable policies,” added Lightman.

In December 2019, the Toronto City Council approved a HousingTO 2020 – 2030 Action Plan that includes building 40,000 affordable rental housing, and the repair and renovation of public housing. The plan requires $23.4 billion from all levels of government, with the city footing $8.5 billion.

Beth Wilson, co-author, Social Planning Toronto.

Photo provided by

Social Planning Toronto

Beth Wilson of Social Planning Toronto and co-author of the report told The Philippine Reporter in an email that they have reached out to city officials and provincial and federal officials to move forward with the policy recommendations.

The Philippine Reporter reached out to the City of Toronto for an update on HousingTO, particularly on the report’s recommendation for a fully funded office of Housing Commissioner. The city’s media liaison replied with a status report that as of September 2020, the city has moved forward with “recommended options and a framework to establish the Housing Commissioner role/ function, to be reviewed by Committee and Council later this year.”

“Through this report, we’re really hoping that we’re providing new data which advocates and policymakers can use to advance these recommendations, through the city of Toronto’s 2021 budget process … and policy developments for provincial and federal governments,” said Lightman.

Comments (0)