Fewer PH-trained doctors able to practice in Canada

Fewer PH-trained doctors able to practice in Canada

Ben Pangilinan, founder and president of the Philippine International Doctors United (PIDrU) (Photo supplied)

SPECIAL REPORT, PART 2: DEPROFESSIONALIZATION OF IMMIGRANTS

August 24, 2021

By Veronica Silva Cusi

The Philippine Reporter

Similar to internationally trained or educated immigrants and refugees, international medical doctors (IMGs) are also faced with challenges in their search for greener pastures in Canada.

For many of these IMGs, there’s another years and years of waiting for their foreign credentials to be recognized, on top of years and years of education and practice.

Due to years of waiting, some Philippine-trained doctors have lost interest in most recent years, said Philippine-trained medical doctor Ben Pangilinan, founder and president of the Philippine International Doctors United (PIDrU), a network of Philippine-trained medical doctors.

The network of doctors from the Philippines has seen its numbers dwindle in recent years, said Dr. Pangilinan. Instead of group meetings with hundreds attending, he now helps members one-on-one. Meetings were held to help each other navigate the licensing process or help Filipino IMGs get into alternative jobs in case they cannot or do not want any more to practise in Canada.

“Some are discouraged [from pursuing opportunities to practise in Canada],” said Dr. Pangilinan on the dwindling number of their membership. He added that over the years, there are fewer IMGs from the Philippines who are admitted to practise in Canada.

The challenge for each IMG maybe different case-by-case, and of course, depending on the province or territory where the IMG wants to practise.

And then there’s the alphabet soup of agencies and associations involved in the licensure and standards processes -– from provincial or territorial Medical Regulatory Authority (MRA) to federal non-profits and governments controlling the budget.

And then there’s the alphabet soup of agencies and associations involved in the licensure and standards processes -– from provincial or territorial Medical Regulatory Authority (MRA) to federal non-profits and governments controlling the budget.

Pangilinan told The Philippine Reporter that education credentials from the Philippines is not the major issue among Filipino IMGs. The challenge for him and many Filipinos who are asking PIDrU for assistance is the competition to get into residency spaces.

During his attempt in the 1990s, he competed to get into one of only 75 residency spots available to thousands of IMGs.

To practise medicine in Canada, IMGs need a verified medical degree, pass written and practice exams, and do medicine training through residency. After the residency, there is also an examination before IMGs can register to practise.

Almost every step of the process — depending on the province or authority — there are fees involved. The fees alone are challenging for IMGs, noted Dr. Pangilinan.

The medical degree of IMGs is verified from the World Directory of Medical Schools (World Directory) where currently there are 48 Philippine medical schools listed. The directory contains a “sponsor note” to indicate that the medical school is accepted in Canada.

Like most regulated professionals, IMGs must show proof of Canadian language proficiency. Luckily for IMGs, the World Directory, contains information on this. The directory indicates if the foreign medical school uses either English or French as the medium of instruction. Therefore, there is no need for further proof of language proficiency, such as the language exams, unlike for other internationally education or trained professionals (IEPs/ITPs) in regulated professions.

Then, IMGs must hurdle the exams – the Part 1 and Part 2 of the Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Examination (MCCQE) for a fee of $1,330 for Part 1, and the National Assessment Collaboration Examination (NAC) for a fee of $2,945.

Examinees go to the Medical Council of Canada (MCC) to sign up for the exams and get their Licentiate of the Medical Council of Canada (LMCC) after passing the MCCQE exams. But the licence to practise in each province or territory is obtained from each jurisdiction.

The MCC has ceased to deliver Part 2 of the MCCQE effective June 2021.

MCC is one of the entities that IMGs encounter to be able to practise in Canada. In their own words, the MCC “plays an important role in the assessment of physicians in Canada.”

The MCC runs the physiciansapply.ca portal where medical graduates and IMGs apply to MRAs.

Aside from the MCC, the Royal College of Canada of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) and the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) also play crucial roles in the licensing and registration of doctors. RCPSC and CFPC set the standards for education and training for physicians in Canada.

Successfully completing the residency program is one of the last steps to get a licence to practice in a jurisdiction.

In the case of Ontario, the MRA is the College of Physician and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO), which “regulates the practice of medicine in Ontario.” Doctors that are allowed to practise in the province must first register with CPSO, which “issues medical licences to those wishing to practise medicine in Ontario.”

“The CPSO is committed to ensuring that physicians licensed to practice in Ontario meet the standards required in provincial legislation and regulation and are able to practice safely and effectively,” said Shae A. Greenfield, CPSO senior communications advisor, in an email to TPR.

The MCC and the RCPSC “play important roles in the larger process for licensing new physicians,” added Greenfield. And there’s the Medical Act, 1991 of Ontario, which set the criteria for candidates’ licensure in the province.

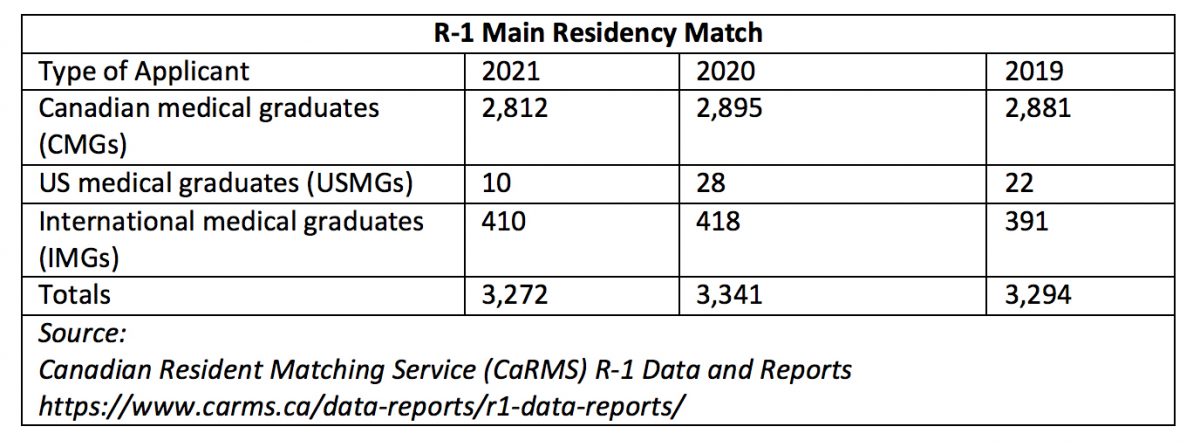

Then there’s the independent national body Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS), which matches 6,000 medical graduates annually to residency posts in Canada using algorithm matching

Dr. Pangilinan said the number of residency spots has increased in recent years, making it relatively easier for IMGs to get a chance to practice in Canada.

Residency applicants are classified according to where they obtained their medical degrees — Canadian medical graduates (CMGs), US medical graduates and IMGs. CMGs get a lion’s share of the residency spots.

In 2021, there were 410 IMGs matched for residency, down from 418 IMGs in 2020 but up from 391 in 2019. The number of residency spots for CMGs also dropped in 2021 to 2,812 from 2,895 in 2020 and 2,881 in 2019. There are also medical graduates from within and outside Canada and the US that are not matched.

Dr. Pangilinan said that Filipino IMGs compete with international Canadian medical graduates due to the lack of spots in medical schools in the country. These are the Canadians who opt to study outside of Canada.

He shared his opinion that this is probably one reason why there are only a few Filipinos who are getting into Canadian residency spots, and therefore, there are only a few Filipino IMGs seeking advice from PIDrU on the licensing process. That is, getting into residency spots has become more competitive for Filipino IMGs because they are also competing with Canadian IMGs.

The number of residency spots are dictated by government budgets since universal healthcare in Canada and medical education are mainly taxpayers’ money.

“Residency positions are provincially funded, hosted by universities and delivered in hospitals and clinics,” said the Canadian Federation of Medical Students (CFMA) in a 2019 pre-budget submission.

The organization representing medical graduates of Canada’s 15 medical schools urged the federal government to increase residency spots to maximize the government’s investments in medical students. The group estimates that each medical student is subsidized by taxpayers for $260,000 each. But one problem preventing Canadian medical graduates from being able to practise medicine is that they are unmatched by CaRMS.

With years of practice, Dr. Pangilinan has come to understand the licensing process vis-à-vis universal healthcare in Canada, especially compared to private sector-led healthcare in the Philippines.

Even in this pandemic when there had been reports of doctor shortage and burnout, the solution is not simply adding more doctors, he said. Again, to add doctors would need more money.

In this pandemic, the CPSO allowed some qualified medical graduates to help out by giving them 30-day Supervised Short-Duration Certificates even though they haven’t completed their residency yet.

After successfully completing residency, IMGs in Ontario then take an exam with either CFPC or RCPSC before they can register with CPSO.

The steps to practise may take years and involve thousands of dollars for IMGs. Residency training can take from two years to seven years.

Dr. Pangilinan said PIDrU also helps Filipino IMGs find alternative professions. Some of them find work in health-related professions, such as insurance clearance, laboratories, nursing, clinical research, and social work.

Comments (0)